The paediatric antiretroviral pipeline

14 July 2011. Related: Pipeline report, Paediatric care.

Polly Clayden

Fewer antiretroviral options exist for children than for adults. Last year’s Pipeline Report introduced a new chapter looking at paediatric formulations of antiretrovirals.1 The chapter detailed some of the hurdles to be overcome to ensure access to antiretrovirals in appropriate forms for children with HIV. It also showed some recent advances.

Since last year’s report, new paediatric development has been scant. Despite incentives and penalties from regulatory authorities to innovator manufacturers designed to ensure that children benefit from these drugs, the disincentives to develop and produce them are considerable. Paediatric drug markets are generally smaller and less interesting to industry than those of adults. In rich countries paediatric HIV has been almost eliminated, meaning there is decreasing demand in these markets.

The best way to deal with paediatric HIV is to prevent it from happening in the first place. At present the elimination of mother-to-child transmission continues to elude most poor countries. Paradoxically, if maternal health and prevention of mother-to-child transmission (PMTCT) programmes become more effective, the advantages in child health this brings will reduce demand further in the paediatric antiretroviral market.

Children are also unaffected by the growing case to provide treatment as prevention.

All this not withstanding, there has been significant progress in recent years in terms of both research and treatment scale-up. United Nations agencies, nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) such as Medecins Sans Frontiers (MSF) and the Clinton Health Access Initiative (CHAI); and UNITAID and other major donors have made a concerted effort to highlight children with HIV and ensure that they have access to the medicines they need.

However, an analysis of the global paediatric antiretroviral market performed in 2010 revealed only a few generic fixed-dose combinations (FDCs) in solid and dispersible forms quality certified by the World Health Organization (WHO) Prequalification Programme or the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) since 2005.2 One quality-certified manufacturer produced most (67%) of these FDCs, and they combine only older antiretrovirals. UNITAID accounted for 97-100% of 2008-2009 FDC market volume.

Price reductions for paediatric FDCs do not have the same potential as those for adults due to small volume. The analysis reported low uptake of FDCs, but this is likely to be largely due to the time required to register products and phase out syrups rather than countries not wanting to use them.

Meanwhile, in 2009 an estimated 2.3 million children were living with HIV. Although an impressive 355,000 children started antiretrovirals that year, 370,000 were newly infected. HIV kills 700 children every day.3

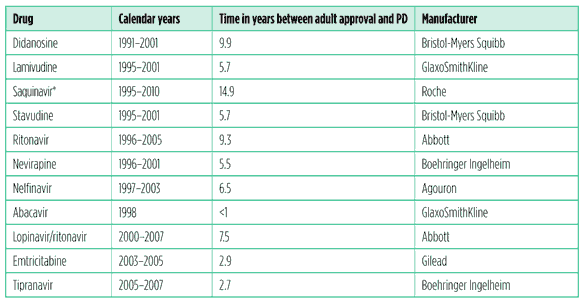

Data produced by CHAI, as part of an internal review, illustrate the paediatric antiretroviral development inertia.4 They show that paediatric determination (PD) – which occurs when manufacturers have completed all FDA requested studies and paediatric exclusivity is awarded – took an average of 6.5 years to achieve after approval for use in adults. This ranged from a laudable less than a year for abacavir to a spectacularly sluggish 14.9 years for saquinavir, which was never approved for children (see Table 1).

Table 1. Time frames between adult approval and PD for antiretrovirals with paediatric exclusivity

Source: CHAI

* Still not approved

When drugs are approved for children, multiple label changes may take place because paediatric populations are studied in sequence. As paediatric investigation plans work in de-escalated age bands, the youngest age groups will have the most prolonged delay in labeling.

Sometimes there is no indication or appropriate formulation for the very youngest children, complicating the implementation of universal treatment as early as possible in infancy.5

Perhaps the most notable change since the 2010 Pipeline Report is that Drugs for Neglected Diseases Initiative (DNDi) has recently entered the field.That this organization considers paediatric HIV to be a neglected disease speaks volumes.6

This chapter gives an update on recent results from clinical trials that will help inform guidance, new approvals and contraindications, the generic and innovator pipelines, ?ones to watch,? and how the new drugs might be used.

What to start with?

WHO guidelines recommend that young children less than two years who have been exposed to maternal or infant nevirapine or other non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NNRTIs) for maternal treatment or PMTCT, start antiretroviral therapy with a lopinavir/ritonavir-based regimen. Nevirapine- or NNRTI-unexposed children, or children older than two years, should start with an NNRTI-based regimen of nevirapine, or efavirenz if the child is older than three years.

Nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor (NRTI) backbones should be one of the following pairs: lamivudine plus zidovudine, lamivudine plus abacavir, or lamivudine plus stavudine. Stavudine is no longer preferred due to its toxicity.

Results from two recent studies may have an impact on future guidance with regard to the use of NNRTIs versus protease inhibitors (PIs) for younger children.

Findings from the IMPAACT P1060 study showed about 20% higher rates of failure at 24 weeks in children aged two months to three years receiving NNRTI-based regimens compared with those receiving PI-based regimens with or without NNRTI exposure.7,8 These results are unsurprising for the NNRTI-exposed children. What is surprising and controversial is the superiority of the PI regimen for NNRTI-unexposed children in this trial – particularly for providers with experience in using NNRTIs in this population in resource-limited settings.

In reality, many caregivers in resource-limited settings prefer nevirapine first-line, even for children exposed to it in utero, due to cost constraints, ease of use, and to preserve lopinavir/ritonavir for second-line.

The NEVEREST trial, also recently presented, showed that children started on lopinavir/ritonavir-based regimens who remained on them had about 10% higher rates of virological failure than children switched to nevirapine.9,10

Currently, WHO guidelines remain unchanged from last year, and opinion differs as to whether it is better to start with a PI or an NNRTI for all young infants. It is argued that many children will still not have been NNRTI-exposed through PMTCT, but this is usually poorly documented. NNRTI-based regimens remain attractive because of cost constraints, formulation, and palatability. PI-based regimens are more potent and can be used in exposed or unexposed children. NEVEREST data suggest it may be possible to switch to an NNRTI after initial suppression with a PI, but this would depend on access to virological monitoring.

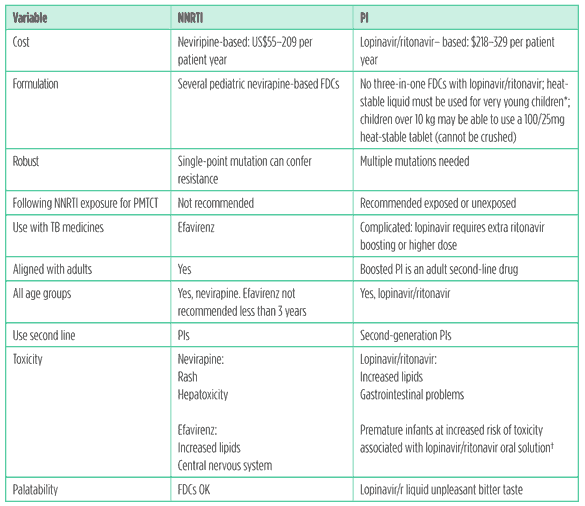

There is agreement, however, that current drugs are far from perfect and a suitable first-line agent, to fit with current guidance, could be a cheaper, more user-friendly PI or a more robust NNRTI suitable for exposed or unexposed children (see Table 2).

As far as older children are concerned, data from the PENPACT-1/PACTG 390 study showed no significant difference at four years with viral suppression with regimens containing either an NNRTI or a PI.11 The PLATO II/Cohere study showed no difference in triple-class failure by initial regimen at four years of age in European children starting treatment with three or more antiretroviral drugs.12

Table 2. Use of NNRTIs compared to PIs in young children in resource limited settings

*At temperatures higher than 25°C, the oral solution of lopinavir/ritonavir requires refrigeration. There are no stability data at temperatures higher than 25°C for lopinavir/ritonavir. Some providers cannot safely prescribe this to infants in households without a fridge.

? Sometimes called ?baby grappa?! The lopinavir/ritonavir syrup contains 42% ethanol and 15% polyethylene glycol.

Induction/maintenance strategies (where people are started on very potent combinations of drugs which are then reduced in number once full viral suppression is achieved) are underexplored in children, – as are questions as to whether a child starting treatment in infancy can ever stop.

Data from several ongoing studies, which will give more information about these issues are still awaited:

- ARROW is investigating a strategy of induction/maintenance – starting with a potent combination of four drugs and maintaining treatment with three versus continual treatment with four drugs.13

- CHER, which demonstrated a big AIDS-free survival advantage from universally starting children on treatment at birth, will continue to follow these children’s progress and look at whether after starting early they can stop treatment after one or two years.14

- BANA and PENTA 11 will determine whether taking CD4-guided planned interruptions disadvantages children on stable therapy.15,16

Recent changes

New FDA tentative approvals and WHO prequalifications

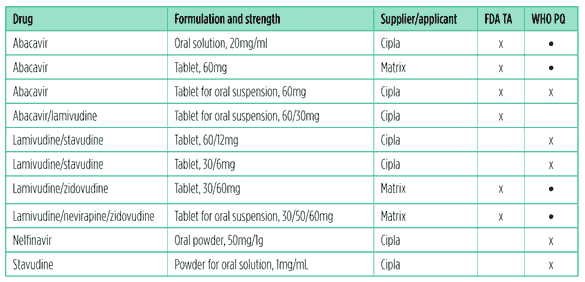

Since last year’s Pipeline Report there have been a number of new tentative approvals and prequalifications (see Table 3).17,18

The good news is that there are several formulations that include abacavir, both stand-alone products and as part of FDCs. Not such good news is that the only PI included is nelfinavir powder, which is barely used in rich countries and is not recommended in guidelines.

Table 3. FDA tentative approvals (TA) and WHO prequalifications (PQ) of paediatric antiretrovirals, 2010?2011

*Formulations already prequalified by the WHO at the time of last year’s review.

FDA warning for lopinavir/ritonavir oral solution use in neonates

In February 2011, the FDA made changes to the Kaletra (lopinavir/ritonavir) oral solution product label to include a warning of potential toxicity in neonates. This was due to life-threatening side effects related to either lopinavir and/or the inactive ingredients propylene glycol and ethanol that had been seen in ten infants, eight of whom were preterm.19,20

This formulation should not be given to neonates before they are of a postmenstrual age (calculated from the first day of the mother’s period until the baby’s birth plus the time from the birth) of 42 weeks and a postnatal age of at least 14 days.

Reduced metabolism by the liver and reduced kidney function in newborns can lead to an accumulation of lopinavir as well as of alcohol and propylene glycol. Preterm babies may be at increased risk because they cannot metabolise propylene glycol.

This warning is important, as both maternal HIV and highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) are associated with preterm delivery (although infants exposed to maternal HAART are a small niche as very few infants will be infected if their mothers receive treatment).

Missing drugs and formulations

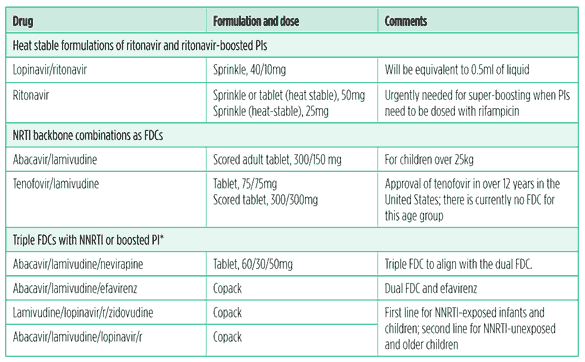

An important formulation in the generic pipeline at present is an alternative to the oral solution of lopinavir/ritonavir.

Cipla is developing a heat-stable sprinkle formulation of lopinavir/ritonavir that may fill this gap. This has been in development for a while now and has undergone a few changes. The sprinkles are tasteless and have a texture similar to granular sugar.

Bioequivalence studies are being undertaken in healthy adults. Pharmacokinetcs and tolerability studies comparing the sprinkles with liquid in 12-month- to three-year old children and with junior tablets in older children, up to four years old will be performed in CHAPAS 2.21

Acceptability of the formulation in young children is very important. The company is still deciding on how to package the 40/10mg dose. Cipla expects to apply for approval with the FDA at the end of 2011.

Darunavir is needed for third-line regimens or for second-line where lopinavir/ritonavir was used first-line. Preclinical studies – showing dangerously high darunavir exposure and in turn adverse events in juvenile rats – meant that paediatric studies were not conducted in children under three years old. Ritonavir boosting of darunavir does not lend itself to easily adjusted doses using WHO weight bands.

A 25mg tablet of ritonavir is included in WHO’s Essential Medicines List but is not yet on the market.22 A 25mg sprinkle formulation is needed for very young children. A 50mg tablet would be useful for super-boosting (giving extra booster to achieve sufficient drug concentration in circumstances where this is reduced by drug-drug interaction) PIs. Super-boosting PIs, when they are given with rifampicin, is not straightforward and urgently needs better guidance and better formulations.

Other generics in development for treating children or considered to be a high priority by the Paediatric Antiretroviral Group of the WHO are shown in Table 4. FDCs that are not stavudine based are also a priority.

Table 4. Paediatric drugs and formulations needed

Source: WHO Essential Medicines List

*It may not be possible to coformulate some combinations, as the individual drugs may have different dosing schedules. Dual blister packaging is preferred in these cases. Emtricitabine is considered interchangeable with lamivudine.

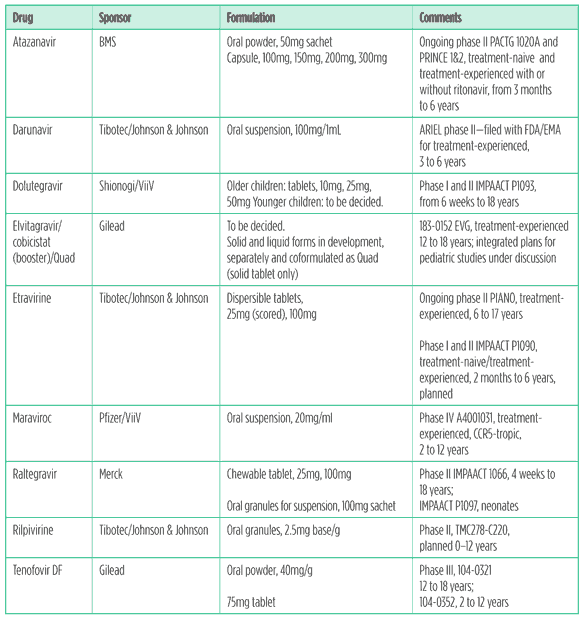

The working group also considered atazanavir, darunavir, etravirine, raltegravir, and tenofovir to be high priority. These drugs are currently approved for adolescents and adults but not for children. The development status and formulations of these drugs are described in Table 5.

As new antiretrovirals become approved, there will be more options for coformulations and copackaging.

Ones to watch: the innovator pipeline

Since last year’s report there have been a few changes:

- The paediatric investigational plan has begun with dolutegravir. (Shionogi/ GSK/ViiV integrase inhibitor S/GSK-572).

- The cobicistat and Quad development plans were given a positive opinion by US and European Union (EU) regulatory agencies.

- The rilpivirine development plan is going ahead with the granule formulation.

- The dossier for the oral suspension of darunavir (boosted) for treatment-experienced children aged three to six years has been submitted to US and EU regulatory agencies.

- Raltegravir will be studied in neonates, first in a passive pharmacokinetic study and then dosed directly.

Nonnucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors

Etravirine: The recommended dose per weight band for children and adolescents aged six to 17 will be based on 5.2mg/kg bid. The company will present 24-week data from the PIANO study in experienced adolescents this year; 48 weeks of the trial will be completed in the last patient later this year.23

An IMPAACT 1090 protocol is in development and the first patient is expected to enroll this year.

There is an upcoming submission for an indication for treatment experienced children and adolescents aged six to17 years and for the 25mg tablet.

Rilpivirine: The PAINT trial is of treatment-naive adolescents, aged 12 to18 years, weighing more than 32kg and receiving 25mg qd plus a background regimen.

TMC278-C220 is an open-label single-arm trial using the granule formulation, planned in children aged two to 12 years. This trial is taking a staggered approach and will study the drug in de-escalated age groups, down to two years of age.24

Nucleotide reverse transcriptase inhibitor

Tenofovir DF: Although tenofovir was approved for adults in 2001 and is a preferred NRTI/nucleotide (Nt)RTI in international guidelines, paediatric development and approval has been slow. Bone toxicity and maturation concerns have been raised about using this drug in children.

The 300mg tablet is approved for adolescents 12 to18 years old weighing more than 35kg in the United States. However, recently the European Medicines Agency (EMA) did not approve an indication for this age group.The decision was based on the GS-US-104-0321 trial of treatment-experienced adolescents, in which tenofovir performed no better than placebo, but this study was underpowered, and on concerns about bone toxicity.

An additional study is ongoing to determine safety and efficacy in children below 12 years of age and under 35kg in weight, in which the 40mg/g oral powder is being evaluated.

A randomised open-label trial, 104-0352, is comparing switching stavudine or zidovudine to tenofovir versus continuing stavudine or zidovudine in virologically suppressed children. Children under 37kg receive the oral powder and those above this weight the 300mg tablet. This trial is ongoing.25

Protease inhibitors

Atazanavir: The capsule formulation is approved for children in the United States aged six years and older who are treatment-naive and weigh 15kg or more and for treatment-experienced children weighing 25kg or more. In the EU it is approved for both treatment-naive and treatment-experienced children aged six years and older and weighing 15kg or more.

Younger children receiving atazanavir boosted with ritonavir are being studied in PACTG 1020A and PRINCE 1 and 2.26, 27

Darunavir: The 75mg tablet is approved when boosted with ritonavir for children over six years of age. The dossier for the oral suspension for treatment-experienced children has been submitted for approval at the following doses: darunavir/ritonavir 25/3mg/kg bid for children weighing 10 to <15kg and darunavir/ritonavir 375/50mg bid for those weighing 15 to <20kg. There is a waiver for children under three years of age.

Integrase inhibitors

Dolutegravir (S/GSK-572): The IMPAACT P1093 study will work with de-escalated age bands of children down to six-week-old infants. The older children will receive tablets and the younger ones the paediatric formulation. A granule formulation is in development.28

Elvitegravir: The 183-0152 study was a phase IB open label nonrandomised trial in treatment-experienced adolescents receiving 150mg qd plus a PI-optimised background regimen. Of the 21 subjects enrolled in the 10-day PK study, 9 of 11 eligible subjects continued elvitegravir plus ritonavir-boosted PI-containing optimised background regimen and completed 48 weeks of treatment.

The paediatric committee of the EMA granted positive opinion toward the cobicistat and Quad paediatric investigational plan in April 2011.

The Quad study will start after a review of data for elvitegravir and cobicistat. Age-appropriate formulations are planned.

Raltegravir: IMPAACT 1060 is investigating this drug in de-escalated age bands. Data for children six to11 years of age and interim data for those two to five years of age, receiving the chewable formulation, have been presented. A dose of 6mg/kg (maximum 300mg) has been chosen. The chewable formulation has lower oral clearance than that of the adult tablet.29

Children under two years of age are now being enrolled in a study to determine the dose of the oral granule formulation.

IMPAACT P1097 is a washout (passive) pharmacokinetc and safety study. This is the first clinical trial of an investigational antiretroviral to look at neonatal pharmacokinetics. Raltegravir crosses the placenta well. It is metabolised primarily by an enzyme in the liver (UGT-1A1), that is immature in neonates. UGT pathways increase in activity hugely in the first weeks of life. This study is recruiting mothers already receiving raltegravir in pregnancy (the infants are not dosed directly). The infants will be sampled at intervals up to 30 to 36 hours after dosing.

After a review of pharmacokinetc and safety data from both trials the company is planning a study of infants born to HIV-positive mothers from immediately after the time of birth until their HIV status has been confirmed.

CCR5 receptor antagonists

Maraviroc: The A4001031 study is ongoing in children two to 12 years old who are infected with the CCR5-tropic virus (virus variants that use the CCR5 receptor for entry).30

Use of this drug requires a tropism assay, as it will not work for people with the CXCR4-tropic virus or in mixed-virus (CCR5/CXCR4) populations.

Further along the pipeline, and one that got stuck

Other promising pipeline drugs, such as the prodrug of tenofovir, GS 7340, and the stavudine derivative festinavir, need to be studied in children as soon as sufficient adult data are obtained.

Over 12 years after efavirenz was approved in adults, there is finally a smattering of data for its use in children under three years of age – including TB-coinfected infants – from IMPAACT P1070 and a couple of other investigator-led trials. Dosing difficulties with large variability remain. The bioavailability of the oral solution is less than 70% of that of the solid forms. High doses (i.e., large volumes of liquid) are needed to achieve adequate exposure in plasma.

This drug is important, as dosing with TB medications – specifically rifampin (rifampicin) – is complicated by boosted PIs and nevirapine. Whether there will be a suitable formulation of efavirenz with an indication for very young children remains to be seen.

Table 5. The innovator pipeline

What to expect in the future

Various ongoing discussions have anticipated how paediatric treatment guidelines might look in 2013 and 2016. This will depend on the approval status of some of the pipeline drugs and the results of ongoing trials.

When to start?

2013: Universal treatment of all young children is anticipated to extend from up to 24 months to up to 36 months (or possibly five years) old.

2016: Universal treatment of all children less than five years old.

Children aged five or older share the criteria for treatment initiation with adults. This is currently at a CD4 count of 350 cells/mm3 or lower, or at any CD4 count in the presence of active TB or hepatitis B.

The change will depend on the results of the INSIGHT START study 001. It is expected to mean starting at a CD4 count of 500 cells/mm3 or lower, or a higher threshold.31

What to start with?

2013: FDCs as much as possible and progressive phase-out of stavudine. Lopinavir/ ritonavir?based treatment for all infants and children under three years of age regardless of NNRTI exposure.

2016: For all children under five years of age; either induction/maintenance of two NRTIs plus a boosted PI to achieve suppression and switch to rilpivirine to maintain suppression (this will depend on NEVEREST results) or two NNRTIs plus dolutegravir with or without switch.

What to use second-line?

2013: If lopinavir/ritonavir is used first, either NNRTI or darunavir (depending on approval – possibly etravirine or raltegravir).

If NNRTI is used first-line, boosted PI as second-line.

NRTIs will depend on the status of tenofovir and what was used first-line. Didanosine will continue to be an option although its phase-out is anticipated.

2016: Induction/maintenance first-line would allow for reuse of boosted PI or douletegravir for second-line, even if these were part of the initial (induction) regimen.

If integrase inhibitors are available, then second-line will probably be a boosted PI plus one of these; if not, then a boosted PI. Hopefully atazanavir and darunavir will be available in appropriate formulations.

If cobicistat is available it may offer an alternative to ritonavir as booster.

What to use third-line?

2013: Two or three regimens of integrase inhibitors (raltegravir), newer boosted PIs (darunavir) and newer NNRTIs (etravirine).

2016: Unclear, but etravirine may be less useful if ripivirine is given as maintenance.

The drugs for neglected diseases initiative

As a postscript to the paediatric pipeline, it deserves a mention that the Drugs for Neglected Diseases Initiative (DNDi) recently decided to add paediatric HIV to its portfolio. DNDi is a needs-driven, nonprofit, research and development organization founded in 2003 by partners including MSF and five public-sector research institutions. As the name suggests, the DNDi develops new treatments for the most neglected patients. DNDi’s focus to date has been on visceral leishmaniases, Chagas disease, sleeping sickness (human African trypansomiasis, or HAT), and malaria. With its partners DNDi has introduced the first new treatment for HAT in 25 years and two inexpensive, field-adapted treatments for malaria.

DNDi was called on by various organizations, including MSF and UNITAID, to apply its expertise to the needs of children with HIV who are under three years old, NNRTI-exposed or -unexposed, and in need of first-line therapy, regardless of prior antiretroviral exposure.

They have come up with a target product profile that includes appropriate dosage forms usable across WHO weight bands, high genetic barriers to resistance, no cold chain needed, well tolerated, no lab monitoring required, and affordable. Any treatment would ideally be compatible with TB medicines.

We welcome DNDi’s involvement and hope that it will usher in a promising new antiretroviral regimen – and at faster pace than we have become used to.

References

- Treatment Action Group, Pipeline Report 2010. New York: Treatment Action Group, 2010.

- Waning B et al. The global pediatric antiretroviral market: Analyses of product availability and utilization reveal challenges for development of pediatric formulations and HIV/AIDS treatment in children. BMC Pediatrics, 17 October 2010;

http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2431/10/74. - UNAIDS, Report on the global AIDS epidemic. Geneva, Switzerland: UNAIDS, 2010.

http://www.unaids.org/globalreport/global_report.htm. - Clinton Health Access Initiative. Personal communication, May 2011.

- World Health Organization. Antiretroviral therapy for HIV infection in infants and children: Towards universal access. Recommendations for a public health approach. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization, 2010.

http://www.who.int/hiv/pub/paediatric/ infants2010/en/index.html. - Drugs for Neglected Diseases initiative. Needs assessment for paediatric R&D. Geneva, Switzerland:Drugs for Neglected Diseases Initiative, 2011.

http://www.dndi.org/diseases/new-disease-areas/781-paediatric-hiv.html. - Palumbo P et al. Antiretroviral treatment for children with peripartum nevirapine exposure. N Engl J Med 2010;363:1510?20. Palumbo P et al. NVP- vs LPV/r-based ART among HIV+ infants in resource-limited settings: The IMPAACT P1060 trial. 18th CROI, Boston, February 2011. Oral abstract 129LB.

- Coovadia A et al. Reuse of nevirapine in exposed HIV-infected children after protease inhibitor-based viral suppression: A randomised controlled trial JAMA 2010;304:1082?90.

- Kuhn L et al. Long-term outcomes of switching children to NVP-based therapy after initial suppression with a PI-based regimen. 18th CROI, Boston, February 2011. Oral abstract 128.

- PENPACT-1 (PENTA 9/PACTG 390) Study Team. First-line antiretroviral therapy with a protease inhibitor versus non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor and switch at higher versus low viral load in HIV-infected children: An open-label, randomised phase II/ III trial. Lancet Infect Dis. 2011;11(4):273?83.

- Pursuing Later Treatment Options II (PLATO II) Project Team for the Collaboration of Observational HIV Epidemiological Research Europe (COHERE). Risk of triple-class virological failure in children with HIV: A retrospective cohort study. Lancet 2011;377(9777): 1580 – 1587

- Medical Research Council, Clinical Trials Unit. ARROW Antiretoviral Research for Watoto.

http://arrowtrial.org/research_areas/ study_details.aspx?s=6. - Violari A et al. Early antiretroviral therapy among HIV-infected infants. N Engl J Med 2008;359.(21)2233?44.

- Baylor International Pediatric AIDS Initiative. BANA II Clinical trial.

http://www.bipai.org/Botswana/clinical-research.aspx. - Paediatric European Network for Treatment of AIDS. PENTA 11 Trial.

http://www.pentatrials.org/p11v5.pdf. - US Food and Drug Administration. President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief: Approved and tentatively approved antiretrovirals in association with the President’s Emergency Plan.

http://www.fda.gov/InternationalPrograms/FDABeyondOurBordersForeignOffices/AsiaandAfrica/ucm119231.htm. - World Health Organization. Prequalification Programme.

http://apps.who.int/prequal/. - US Food and Drug Administration. Kaletra (lopinavir/ritonavir) oral solution label changes related to toxicity in preterm neonates. February 2011.

http://www.fda.gov/ForConsumers/ByAudience/ForPatientAdvocates/HIVandAIDSActivities/ucm244639.htm. - Boxwell D et al. Neonatal toxicity of Kaletra oral solution – LPV, ethanol, or propylene glycol? 18th CROI, Boston, February 2011. Poster abstract 708.

- Current Controlled Trials Ltd. Children with HIV in Africa – Pharmacokinetics and adherence of simple antiretroviral regimens (CHAPAS-2).

http://www.controlled-trials.com/isrctn/pf/01946535. - World Health Organization. WHO model list of essential medicines for children. 3rd list. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization, 2011.

- International Network for Strategic Initiatives in Global HIV Trials (INSIGHT). INSIGHT Home.

http://insight.ccbr.umn.edu/.

TMC125-TiDP35-C213: Safety and Antiviral Activity of Etravirine (TMC125) in Treatment-Experienced, HIV Infected Children and Adolescents.

http://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT00980538 - TMC278-TiDP38-C213 (PAINT): An Open Label Trial to Evaluate the Pharmacokinetics, Safety, Tolerability and Antiviral Efficacy of TMC278 in Antiretroviral Naive HIV-1 Infected Adolescents.

http://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT00799864 - Safety and Efficacy of Switching From Stavudine or Zidovudine to Tenofovir DF in HIV-1 Infected Children (Ages 2- <12).

http://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT00528957 - PRINCE: Study of Atazanavir (ATV)/Ritonavir (RTV) (PRINCE1).

http://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01099579 - Phase IIIB Pediatric ATV Powder for Oral Use (POU) (PRINCE2).

http://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01335698 - Safety of and Immune Response to GSK1349572 in HIV-1 Infected Infants, Children, and Adolescents.

http://clinicaltrials.gov/ ct2/show/NCT01302847 - Safety and Effectiveness of Raltegravir (MK-0518) in Treatment-Experienced, HIV-Infected Children and Adolescents

http://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT00485264 - An Open Label Pharmacokinetic, Safety And Efficacy Study Of Maraviroc In Combination With Background Therapy For The Treatment Of HIV-1 Infected, CCR5 -Tropic Children.

http://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT00791700

Additional sources

Untangling the Web of Antiretroviral Price Reductions:

http://utw.msfaccess.org/