UK cascade data cautions UNAIDS 95:95:95 targets: re-engaging people in care

1 June 2023. Related: Conference reports, Treatment strategies, Activism & advocacy, BHIVA 29th Gateshead 2023.

Simon Collins, HIV i-Base

BHIVA 2023 included several talks in a symposium about the UK treatment cascade. Results show that UNAIDS targets can significantly overestimate the actual provision of HIV care and can inadvertently produce an overly optimistic view of current services. [1]

BHIVA 2023 included several talks in a symposium about the UK treatment cascade. Results show that UNAIDS targets can significantly overestimate the actual provision of HIV care and can inadvertently produce an overly optimistic view of current services. [1]

The presentations included strategies to retain people in care, up to 20% of whom might currently be excluded from 95:95:95 estimated targets. There are many complex reasons that prevent people from prioritising their own HIV health, often for many years. Bringing people back into care also makes economic sense and helps with achieving goals for HIV prevention.

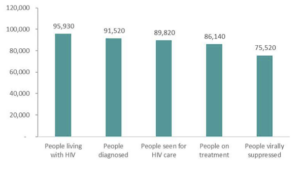

Although the UK is one of the first countries to report that more than 95% of people living with HIV are diagnosed, on treatment and have an undetectable viral load, up to 18,000 people might be missing from this data.

This is because there are different denominators for each metric, because the cross-sectional snapshot only refers to data from the previous year (similar to an on-treatment analysis) and because of positive adjustments for missing data.

Why third target in the UK might only be 88%

The plenary talk by Dr Ann Sullivan from the Chelsea and Westminster Hospital, using data from England for 2021, reported top-line cascade results of 95.4% for testing, 98.7% for accessing care and 97.8% for achieving undetectable viral load. [2]

The talk also presented differences within the cascade linked to demographics, and highlighted different results by age, sex, sexuality, ethnicity and other factors.

But instead of 97.8, the third metric might only be 88% – also explained by Cuong Chau later in the session. The results are still impressive, but 88% shows how much still has to be done.

The first UNAIDS 95% target is the percentage of people living with HIV who have been diagnosed. In England, an estimated 95,930 people were living with HIV in 2021, of whom 95.4% were diagnosed. This left an estimated 4,400 people who were not yet diagnosed, with a 95%CI range of 3,500 to 6,100.

The second target is not based on percentage of people diagnosed, but only those who connected to care in the previous year and who are on ART. This is based on HARS data (HIV and AIDS Reporting System) from people who were registered at and attended an HIV clinic in the previous year. These records need to also have either a treatment status update or an undetectable viral load (assuming continued use of ART).

The third target relating to treatment efficacy is the percentage of people who have an undetectable viral load, but the denominator is also the subset of people on ART who have a viral load test result recorded during the last year. Rather than being the number of people in care or the number diagnosed, this factor depends on engagement with viral load testing and tends to enter missing data as a positive response.

The definitions for each of these stages don’t account for the significant minority of people who disconnect from care, or that they might often remain out of care for many years.

Taken together, a significant number of people are not counted when calculating the UNAIDS targets, and between 12,000 and 28,000 people in England might have detectable viral load, see Table 1.

Table 1: Estimates of people in England with detectable viral load (2021)

| lower estimate | upper estimate | |

| Not diagnosed. | 4,400 | 6,100 |

| Diagnosed but not linked to care. | 147 | 147 |

| In care but not on ART. | 1195 | 1500 |

| On ART but not suppressed. | 1799 | 1799 |

| On ART, suppressed but no recent VL. | _ | 2621 |

| Not retained in care. | 4118

(previous 15 mo). |

13,963

(previous 5 yrs). |

| Total | 11,659 | 28,130 |

- Using the upper 95%CI for people undiagnosed drops the first column from 95.4% to 93.7% and counting missing viral load data as detectable drops viral suppression in the third column from 97.5% to 90.5%.

- Assuming missing data is a negative outcome, the percentage linked to care drops from 98% to 94% and drops viral suppression from 97% to 82% (or only 77% using the upper estimate of those undiagnosed).

Table 1: Continuum of care in England (2021)

Successful examples to re-engage in care

The second talk in this session by Kate Childs from Kings College Hospital, continued the theme of missing data by showing how the cascade can reverse, for example if viral load rebounds on ART, and if people discontinue ART or fall out of care completely. [3]

It also included new data from a project first presented at BHIVA last year, that tries to contact people once they have become lost to care for more than a year.

This included 7092 people living with HIV who were registered for treatment in Lambeth, Lewisham and Southwark in South London. Of these, 2275 had not been seen in the previous 12 months, 521 of whom were identified by UKHSA as still in care and another 930 of whom were identified as in care or confirmed to have either died or left the country.

Of the remaining 824 people who are potentially disconnected from care, intense tracing efforts were able to re-engage with 153 (18%).

The characteristics of these 153 people included a median CD4 of 305 cells/mm3, with 48/153 <200 cells/mm3. The median age was 46, just over half (57%) were women and 71% Black African/Caribbean. Just under half (45%) came from the lowest 20% of defined bands of social deprivation, showing significant health inequalities related to ethnicity, sex and poverty.

Reconnecting to care was successful with durable outcomes reported this year for many. Of the 153 people who re-engaged between July 2020 and December 2021, 117/153 (76%) were still in care a year later, most at the same clinic. Of the 97 with recent viral load data, 63/97 (65%) had undetectable viral load <50 copies/mL and 74% were <200 copies/mL.

Common issues linked to being lost to care helped explain some of the reasons that prevented people from prioritising their own health.

In the short-term, missing an HIV appointment or even disconnecting from care doesn’t usually directly affect how well someone feels. They might even feel better if not having to take meds is seen as one less thing to worry about, but it will increase the risk of much more serious and debilitating outcomes later. And this talk included devastating real-life examples.

These competing needs include financial poverty, having a difficult housing and immigration status, living with a fear of disclosure, and having sole responsibility for looking after children. Some people reported being in a relationship that undermined the importance of HIV and care. These factors also overlapped with issues of mental health, complications from drug and alcohol use, and perhaps never having HIV-related illness.

Overcoming barriers to engaging in care

The presentation highlighted several ways that tried to overcome barriers to attending HIV clinics.

- Enabling appointments at venues outside the traditional clinic setting and at a wider range of times.

- Having a dedicated smartphone for the clinic to enable easier communication, including by Whatsapp messaging, emails and calls that don’t involve going through a switchboard, which can help with continuity of care.

- Working closely with services providing mental health, social work and drug and alcohol support and ensuring access to peer support.

- Using a case management approach that could include supermarket and travel vouchers.

- Helping people register at new clinics and GP surgeries, especially if they move to live in a different region.

- The potential role of positive public health campaigns to ‘welcome back’ people who are currently disengaged. Also, outreach to communities where HIV stigma is still a significant issue.

In one case, the repeated contact and messaging by the clinic eventually convinced someone that HIV care was important and that their health mattered.

This highly intensive and individualised approach is not currently funded, even though the numbers of people lost to care are already likely to be significantly higher than those who are not yet diagnosed.

However, UKHSA now actively works to identify people who have been lost to care and these cases are reported back to every individual clinic to check as part of the annual dashboard. To be effective, individual clinics need to engage with this process and also report back to UKHSA.

Finally, Cuong Chau from UKHSA presented a talk on the agency’s responses that included extending the window from 12 months to 15 months to allow for retention in care, including new data fields for people who leave the UK or who are no longer seen at the clinic, and data tracing for people being seen at alternative clinics. [4]

This also expanded on considerable work involved in reporting lost cases back to all clinics as part of the HIV dashboard mentioned above and on how to interact with UKHSA. So far this has led to updating CD4 baseline data for 261 people, adding viral load results for almost 5000 people (80% of whom were undetectable) and identifying 721 people as still being in care.

However, only 63% of clinics responded to dashboard follow-up and the talk gently encouraged all clinics to actively engage.

comment

This focus on helping people to re-engage with care is likely to affect all clinics.

One recommendation is to include a named contact person responsible for overseeing people out of care at each site. Another includes the urgency of appropriate funding.

Misconceptions about the way UNAIDS metrics are calculated will also affect global reporting of the 95:95:95 targets as they steadily approach 100%.

Although reaching these goals is a considerable achievement, significantly underestimating the actual levels of care risks undermining this success.

References

- BHIVA 2023. The Care Cascade: where should we focus next? Symposium. Tuesday 25th April 2023.

https://vimeo.com/822989830 (symposium link)

https://www.bhiva.org/SpringConference2023Presentations (programme webcasts) - Sullivan A. Overview of the cascade: where should we focus next? BHIVA Spring Conference 2023 (BHIVA 2023), 24–26 April 2023, Gateshead.

https://www.bhiva.org/file/645ba42c58ceb/Ann-Sullivan.pdf (PDF slides) - Childs K. People living with HIV not in care: time to act!

https://www.bhiva.org/file/645ba42c7a8c8/Kate-Childs.pdf (PDF slides) - Mower R. Can we identify patients at risk of not being in care?

https://www.bhiva.org/file/645ba42bd677b/Veronique-Martin.pdf (PDF slides)

This report was first posted on 14 May 2023.