IAS strategy for an HIV cure (2021): an easy-to-read Q&A

1 December 2021. Related: News.

Introduction

World AIDS Day 2021 includes a new focus on finding a cure for HIV.

This is helped by a new review on cure research. [1]

The report, published in the medical journal Nature Medicine, is from the International AIDS Society (IAS).It summarises scientific advances over the past five years. And it also sets a Global Scientific Strategy for the next five years.

The report, published in the medical journal Nature Medicine, is from the International AIDS Society (IAS).It summarises scientific advances over the past five years. And it also sets a Global Scientific Strategy for the next five years.

Although a cure for HIV sounds simple, it is a very difficult challenge. Finding a cure involves solving many detailed problems. And even after years of research, there are still many things that scientists are just beginning to understand.

But there is real hope that a cure will be found. And researchers know that to be successful, any cure will need to be widely available, and to people in all countries.

What is the IAS cure report?

Every five years the IAS publishes a summary of cure-related research.

This third version was published on 1 December 2021 and covers over 170 new studies.

The first reports were in 2012 and 2016 and are also free to read online. [2, 3]

The first reports were in 2012 and 2016 and are also free to read online. [2, 3]

As these reports are quite technical, two other summaries are available. One is for medical journalists and advocates who are used to reporting HIV cure research. [4]

The other is in everyday language for general readers. This will be easier for most people living with HIV. [5]

The everyday language version is below as a Q&A. It can also be an easier introduction to both the main technical paper and the summary for journalists.

The report starts by saying why a cure is important.

Why is a cure important?

HIV treatment (called ART) is really effective. It means that most people can lead long and active lives.

ART reduces HIV viral load to tiny levels. When viral load is undetectable this even prevents sexual transmission. But HIV is still present in sleeping cells that means ART cannot be stopped.

- ART still needs to be taken lifelong.

- It usually involves taking daily pills and not missing doses.

- Some people get side effects.

- Some people still don’t access ART.

- ART is also either expensive or depends on international funding. This maybe costs $3 billion a year.

- A cure is always better than treatment.

So research into a cure gives us hope, and hope is always a good thing.

Why a cure is so difficult: the HIV reservoir

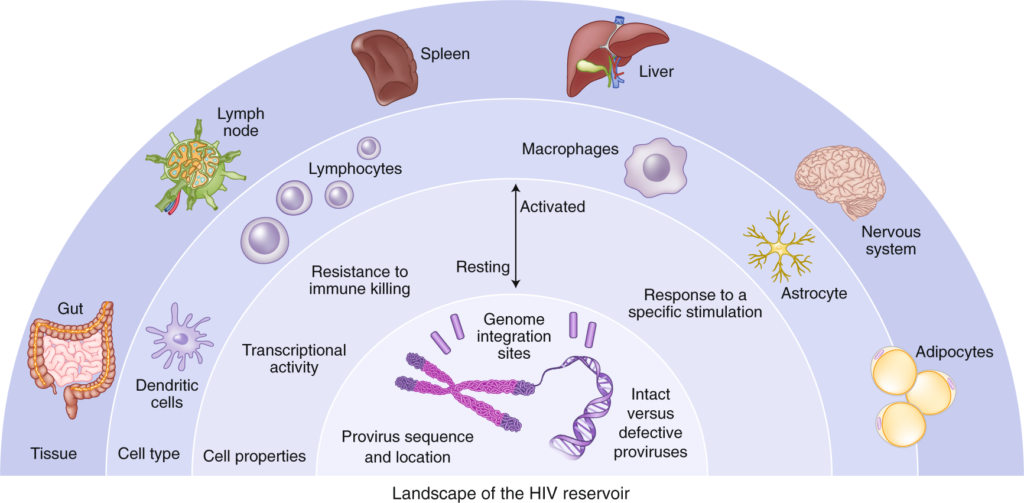

HIV is difficult to cure because the virus gets integrated into some of our immune cells soon after infection.

It then hides in these sleeping immune cells – and cannot be reached by ART.

These cells are called the HIV reservoir and they are the main focus for cure research.

The HIV reservoir includes different types of cells and in different parts of the body. HIV is integrated into our DNA in these cells. Most cells are in a resting state that is not reached by ART. (c) Nature Medicine.

Some of these cells are in different parts of our bodies. Definitely in lymph nodes, but also maybe cells in the gut or liver or brain.

The reservoir occurs very early – within weeks of infection. This is before most people even know they are HIV positive. And some of these cells can sleep for 20, 30 or 40 years.

These sleeping cells do not do any harm. This is the normal state for most immune cells. The problem is that they can wake up at any time.

It they wake up when taking ART, there is also no problem. But if ART is stopped, the waking cells will cause viral load to rebound to really high levels again. Even if viral load has been undetectable for more than 10 years.

Are many researchers really looking for a cure?

Yes. Many different research groups have always been working to cure HIV.

This expanded dramatically over the last ten years. Funding has also increased to support this.

Researchers are also working together. This is so that different groups don’t all repeat the same studies.

Cure research is a good example of scientists working together on a common goal. This includes agreeing on how and what should be measured when defining cure research.

What are the main research goals?

The main report explains the different approaches to a cure.

These include:

- Understanding and measuring the HIV reservoir.

- Understanding how the immune system controls HIV in different ways.

- Inventing new ways to target the HIV viral reservoir.

- Inventing ways to either adapt or change the immune system.

- Developing better tests for all aspects of cure research.

- A new focus on cure research for children.

- Looking at social aspects of cure research. For example, including the views of people living with HIV and making sure that the studies are safe and ethical.

What are the latest advances?

The last five years has included many important advances.

- We now know much more about the viral reservoir.

- There are more rare cases of people who are now cured. And this has been for very different reasons. This includes two elite controllers who are were cured without treatment.

- New drugs and strategies have been studied.

- We have a better understanding of how HIV hides from ART. And also why it comes back if ART is stopped.

Understanding the HIV reservoir

Other advances include a better understanding of the HIV reservoir.

This was first thought to be a fixed group of cells. Even with ART the reservoir was not thought to change much over time.

We now know that:

- The reservoir is much more dynamic than first thought.

- That new cells are being added to the reservoir over time.

- That new cells are being made an unexpected way. Instead of waking up first to replicate, they make copies of themselves while still sleeping. So they can do this while still avoiding ART.

- Researchers have developed new ways to measure and study the reservoir.

- There might be also differences in the reservoir in women compared to men.

- That activating the reservoir has worked in mouse studies. For many reasons, other animal studies are difficult for cure research (especially in monkeys).

Targeting the viral reservoir: three approaches

There are four different approaches to the HIV reservoir.

- To activate and clear these cells. This is called ‘shock and kill’ or ‘wake and clear’. Different drugs are being tested to see if they shock the sleeping cells to wake up so that ART can clear HIV. This has only been successful in mouse studies.

- To try to stop the sleeping cells from waking up. This is called ‘block and lock’. So the sleeping cells with HIV would be locked down.

- To reduce the reservoir and to then get the immune system then to control HIV without ART. This might use a vaccine or monoclonal antibodies and is called ‘reduce and control’.

- Using gene therapy (genetic scissors) to cut HIV out of the infected cells.

All four approaches are complicated. They involve finding the few cells that have HIV without damaging the majority of other immune cells that are still resting.

Another challenge is that when immune cells are sleeping there is no easy way to know whether or not HIV is inside.

People who have been cured or who are in remission

It is exciting that a few people have now been cured of HIV. Although this was in ways that most of us can’t use, these rare cases are important to know about.

- Three cases using gene therapy. This involved stem cell transplants – a very risky and difficult process. [6, 7, 8, 9]

- Two elite controllers where HIV can now longer be found. [10, 11, 12]

- One case where HIV had been very advanced, but without explanation, seems to have been cured. [13,14]

- Examples of people who control HIV after having stopping ART (though these are not cures). [15, 16]

The cases using bone marrow transplant were as a complex treatment for cancer. They showed one way that HIV could be cured but this is much too dangerous to be more widely used. These were the patients from Berlin (Timothy Ray Brown) in 2008 and from London (Adam Castillejo) and Düsseldorf (both in 2019). [6, 7, 8]

These people also actively supported research. They often agreed to have many difficult additional tests. Some also provided a public face for an HIV cure. Although Timothy Ray Brown died last year, this was due to complications related to cancer and not because of HIV. He was an inspiring activist for over ten years and is really missed. [9]

There have also been a two reports of natural cures which has never happened before. The first, last year, was a woman in California who had been HIV positive for over 30 years (Loreen Willenberg). She is part of a study with over 60 other ‘HIV elite controllers’. These are people who keep a high CD4 count and undetectable viral load without ART. After searching for HIV in billions of cell samples, including those that were sleeping, researchers could no longer find active HIV in this person. This gives hope that other elite controllers might also be cured in the future. [10]

Rather than having a strong immune response, this case is being explained by HIV joining a remote section of human DNA that was not active. These inactive sections of DNA are called ‘gene deserts’. [11]

Finally, two different women from Argentina have also been reported as cured. Both have so far decided to stay anonymous.

The first was only reported a few weeks, after the IAS cure paper had gone to press. This case, called the Esperanza patient, is an elite controller who has been HIV positive for more than seven years. She only used ART during pregnancy, and detailed tests have not been able to find active HIV, even in sleeping cells. [12, 13]

The second was reported in 2014 but there is little follow-up information. The explanation in this second case is not clear. It is unusual because the person had previously been very ill with complications of advanced HIV. Also, because they now test HIV negative using antibody tests. [14, 15]

Although not cures, there have also been rare cases of people who control HIV after stopping ART. For some people this might be close to a cure, because they stay healthy without ART for many years. Sometimes this is referred to as a functional cure – but viral load has rebounded in some of these people. This means they continue to need monitoring, even without ART.

These cases are different from elite controllers because they needed ART and this was often started soon after infection. It includes a group of over 20 French patients called the Visconti cohort. Some of these people have kept an undetectable viral load for more than ten years after stopping treatment. Some however, have needed to restart later. These cases are interesting to study but they are not cured because HIV was still easy to find in their cells. [16, 17, 18, 19]

Targeting the immune system

Some research groups are targeting the immune system.

Recent advances include a few examples when an immune-based treatment has been able to control HIV without ART. In two cases this was for longer than one year. [20]

This approach uses monoclonal antibodies, sometimes in combination with other drugs to produce a vaccine-like immune response.

Other groups are focussed on cell and gene therapies to produce immune response to HIV. This includes cutting-edge technology that are being used for some cancer treatments. For example, using gene editing with CRISPR/Cas9 or (CAR)-T cells.

All these approaches will continue over the next five years.

What about a cure for children and young people?

Finding a cure for children is just as important as for adults, maybe more so.

- People who were born with HIV, or who became positive soon after, they have a different immune history.

- This will be different to adults whose immune system was fully developed before they became HIV positive.

- Treatment is also often started much sooner compared to adult infections.

- This means that children could be living with HIV for 70 or 80 years, or longer. As treatment is often started soon after birth, they will also be using ART for a much longer time.

Some cure approaches should probably be shown to be safe in adult studies first. But cure research in general needs to include specific issues for young people, and not lag behind, waiting for an adult cure first.

Ethical issues of cure research

Cure research involves more than just medical and scientific challenges.

It needs to include the views and feelings of people living with HIV. And this needs to include the wider communities – not just a few community activists.

- What do we want in a cure?

- What are the most important things that would improve our lives?

- How important is it to be able to live without medicines?

- How important is it to remain safe to partners (similar to U=U on treatment)?

- Does it matter if we still test HIV positive?

- How to manage the difference between and HIV cure and remission.

There are also ethical questions about cure-related studies. If there is no actual chance of a cure, this needs to be clear to participants. This involves different issues for infants, young children, adolescents and adults.

We need to make studies as safe as possible. But some studies involve stopping ART with a treatment interruption. One recent study included a participant who became reinfected with drug-resistant HIV when off-ART. Another reported that an HIV negative partner became positive during the interruption.

A cure means that HIV is gone for good – and that it will not come back. But a period of remission means that HIV might come back, even after many years. If this was to happen, viral load could rebound quickly. The shows the importance of a having a home viral load test – something that is not yet available.

How long will it take to find a cure?

This is the question that everyone wants to know. It is also one of the questions that no-one can answer well.

- Although scientists say that a cure will come, it is difficult to say when.

- This is likely to be at least ten years away. But a lot can happen in ten years.

- We might be lucky and have an unexpected breakthrough much earlier.

What are the key conclusions?

The report has several key messages and these are a good summary.

- Finding a cure is important and it is needed. But this goal is achievable.

- Researchers are working together from many countries to make this happen.

- The last five years have seen significant scientific advances.

- A cure is likely to involve several different approaches and treatments.

- It also needs to actively involve the wider communities of people living with HIV. This includes both adults and children.

- To be successful, a cure will also need to be widely available to people in all countries.

- Unless there is an unexpected advance, this is likely to take at least another ten years.

IAS and the writing group

The International AIDS Society was founded in 1988. It is the leading scientific and medical organisation focused on HIV. It includes more than13,000 members from over 170 countries. It has a wide educational programme that includes running the large international AIDS conferences.

www.iasociety.org

The writing group for this paper included more than 40 experts from many different countries. The group is led by Professor Sharon Lewin and Dr Steven Deeks and the group also included community advocates.

The Q&A summary was written by Simon Collins, Richard Jefferys, Udom Likhitwonnawut, Siegfried Schwarze and community members of the writing group for HIV i-Base (www.i-Base.info).

Selected references

- IAS Scientific Working Group on HIV Cure. Research Priorities for an HIV Cure: IAS Global Scientific Strategy (2021). Nature Medicine (1 December 2021). DOI: 10.1038/s41591-021-01590-5.

https://www.nature.com/articles/s41591-021-01590-5 - IAS Scientific Working Group on HIV Cure. Towards an HIV cure: a global scientific strategy. Nat Rev Immunol 12 607–614 (2012). DOI: 10.1038/nri3262. (20 July 2012).

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3595991 - IAS Towards a Cure Working Group: Global Scientific Strategy Towards an HIV Cure 2016. Nat Med. 2016 Aug 22(8): 839–850. doi:10.1038/nm.4108. (11 July 2016).

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5322797 - Summary for medical journalists. Also in French, Portuguese and Spanish.

https://www.iasociety.org/wad2021 - IAS strategy for an HIV cure (2021): an easy-to-read Q&A

https://i-base.info/ias-towards-an-hiv-cure-2021 - Stem cell transplant from HLA-matched CCR5-delta 32 deleted donor suppresses viraemia in recipient for 8 months without HAART. HTB (01 April 2008)

https://i-base.info/htb/1819 - The London Patient tells his story as second person cured of HIV. HTB (20 March 2020).

https://i-base.info/htb/37294 - UK patient likely to be the second person cured of HIV: two further cases at CROI 2019 of HIV remission after allogenic stem cell transplants. HTB (12 March 2019).

https://i-base.info/htb/35767 - In memory: Timothy Ray Brown – the Berlin patient, the first person to be cured of HIV. HTB (14 October 2020).

https://i-base.info/htb/39020 - Roehr B. The world’s first known person who naturally beat HIV goes Public. (17 October 2019).

https://leaps.org/exclusive-the-worlds-first-known-person-who-conquered-hiv-without-medical-intervention-goes-public - Casado, C. et al. Permanent control of HIV-1 pathogenesis in exceptional elite controllers: a model of spontaneous cure. Sci. Rep. 10, 1902 (2020).

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32848246 - Turk G et al. A Possible Sterilizing Cure of HIV-1 Infection Without Stem Cell Transplantation. Annals Internal Medicine. (16 November 2021).

https://doi.org/10.7326/L21-0297 - Highleyman L. A Second Woman May Be Naturally Cured of HIV. (15 November 2021).

https://www.poz.com/article/second-woman-naturally-cured-hiv - Urueña A et al. Functional cure and seroreversion after advanced HIV disease following 7-years of antiretroviral treatment interruption. AIDS 2016 conference. Poster MOPE016.

https://www.abstract-archive.org/Abstract/Share/17991 - Argentine Woman Appears Free of HIV Long After Stopping Treatment. Poz magazine. (16 February 2021).

https://www.poz.com/article/argentine-woman-appears-free-hiv-long-stopping-treatment - Stack M. Towards an HIV cure: early developments reported. HTB (1 August 2012).

https://i-base.info/htb/19834 - Hocqueloux L et al. Intermittent viremia after treatment interruption increased risk of ART resumption in post-treatment HIV-1 controllers. ANRS VISCONTI study. International AIDS conference, 2018. Poster abstract WEPDB0104.

https://www.abstract-archive.org/Abstract/Share/76729 - Kinloch SI et al. Aviremia 10-year post-ART discontinuation initiated at seroconversion. 2015 Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections (CROI 2015), 23-26 February 2015, Seattle. Poster abstract 377.

http://www.croiconference.org/sessions/aviremia-10-year-post-art-discontinuation-initiated-seroconversion - Casado, C. et al. Permanent control of HIV-1 pathogenesis in exceptional elite controllers: a model of spontaneous cure. Sci. Rep. 10, 1902 (2020).

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32024974 - Dual bNAb maintains viral suppression for median 21 weeks off-ART. HTB (13 November 2018).

https://i-base.info/htb/35248