HIV diagnoses in UK drop for third year: among all ages, risk groups, and ethnicities and across most UK regions

19 September 2018. Related: Special reports, HIV prevention and transmission.

Simon Collins, HIV i-Base

Simon Collins, HIV i-Base

Preliminary data, press-released by Public Health England (PHE) on 4 September (ahead of the full report due in December), show that HIV diagnoses dropped by 17% in 2017 compared to 2016. [1]

The accompanying press release notes that this is the second year that overall diagnoses have fallen by such a significant amount, although this is technically the third year of reductions. [2]

Crucially, the latest data show a consistent trend for lower numbers of HIV diagnoses across all demographics, and for many groups these have continued for two or three years.

In the last year, figures have reduced for all major risk groups, including gay men, heterosexual men and women, and people who inject drugs. With few exceptions, this trend is also seen across all age groups, for all ethnicities and in all geographic regions of the UK. See Table 1 for selected results.

Overall, HIV diagnoses fell by 17% last year and by 13% the year before, with 4363 people diagnosed during 2017 compared to 6043 in 2015.

These results are remarkable. This is the first time in context of modern ART, that HIV figure dropped so significantly. It is in the context of the lack of impact of HIV prevention campaigns for the previous 15 years since 2000.

The summary report highlights the reductions in gay men as being a drive behind the size of the reductions. From 2008 to 2014 diagnoses in gay and bisexual men had been increasing every year. Since 2015, diagnoses in London clinics dropped by 44% and outside London by 28%.

As with the reductions reported last year, although driven by the drop in gay and bisexual men in London, it is notable that similar percentage drops occurred across the UK, and in other risk groups.

HIV diagnoses dropped by 24% in London, 14% in the Midlands and East England, 12% in the North of England, 21% in the South of England, 20% in Wales and 20% in Scotland. In Northern Ireland, although numbers are relatively low, diagnoses increased by 9% (from 76 to 83).

The changes since 2015 are likely to reflect multifactorial changes in HIV treatment and prevention.

- The move to more frequent routine testing (1-3 monthly, rather than annually) in higher risk groups.

- Easier access to modern sexual health clinics – including walk-in and out-of-hours services.

- Earlier use of ART, including during primary HIV infection and especially since the START study results in 2015.

- Better and more effective ART, that allow easier adherence, fewer side effects, and quicker and more durable viral suppression.

- Growing acceptance of the impact of having an undetectable viral load on stopping HIV transmission.

- Increasing use of PrEP among gay men at highest risk. This was both from the PROUD study and from buying PrEP online as a result of community awareness campaigns.

Other notable results include:

- Significant reductions in diagnoses in young people, reduced by 32% and 35% for ages 18-24 and 25-34 respectively, comparing over two years from 2015 – 2017.

- 17% reduction in HIV-related deaths in 2017 and 35% reductions compared to 2014.

- 22% reduction in numbers of people diagnosed with a proximal CD4 <350 in 2017 and 39% reduction compared to 2014. This last point is complicated however by the lack of change in the overall percentage of late diagnoses each year. This figure varies by risk group (roughly 31% for gay men, and 50-60% for heterosexual men and women, and when injection drug use is the risk factor). These percentages have not changed.

For detailed breakdowns by gender, age, ethnicity, risk group, geographic region and CD4 count please refer to the full data tables.

Table 1: Selected results on HIV diagnoses, and percentage reductions from previous year (PHE data to end 2017)

| 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | |

| Total diagnoses | 6185 | 6043

(–3%) |

5280

(–13%) |

4363

(–17%) |

| Gay men | 3360 | 3390

(NS) |

2820

(–17%) |

2330

(–17%) |

| Heterosexual women | 1440 | 1310

(–10%) |

1190

(–10%) |

1040

(–13%) |

| Heterosexual men | 1090 | 1030

(NS) |

1000

(NS) |

770

(–23%) |

| PWID | 150 | 210

(+40%) |

150

(–29%) |

140

(–7%) |

| 16-24 yo | 732 | 734

(NS) |

534

(–28%) |

502

(–6%) |

| 25-34 yo | 2051 | 2031

(NS) |

1616

(–21%) |

1326

(–18%) |

| >65 yo | 210 | 162

(–23%) |

190

(+17%) |

145

(–24%) |

| AIDS at diagnosis | 281 | 335

(+19%) |

279

(–17%) |

230

(–18%) |

| deaths | 650 | 527

(–19%) |

513

(–3%) |

428

(–17%) |

| <350* | 5060 | 4742

(–7%) |

3980

(–17%) |

3118

(–22%) |

* Although numbers for late diagnosis has consistently fallen, the annual percentages of diagnoses that are late is unchanged: ranging from ~31% in gay men, 50-60% in heterosexuals and 50% in people who inject drugs.

NS = no significant change from previous year.

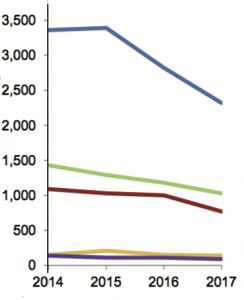

Figure 1: New HIV diagnoses by year of diagnosis and probable exposure route: UK, 2008-2017 *

comment

The UK surveillance data is an essential project and the team should be congratulated for their consistently impressive work. As a result, the UK has one of the most timely and comprehensive HIV surveillance datasets that has been reporting detailed demographics on HIV incidence for more that 25 years.

It is therefore unfortunate that the strengths of the data are misrepresented by the narrative in the accompanying report and press release.

The press release issued by PHE continues to refer to condoms as the only prevention option, ignoring the importance of both treatment as prevention and PrEP, which are both significantly more effective than condoms at preventing HIV.

The quote from Professor Noel Gill as Head of the STI and HIV Department at Public Health England, referring only “to consistent and correct condom use” does not reflect the reality of modern HIV prevention strategies.

The press release and summary report – the primary source for mainstream news reports – both show little enthusiasm for the impact of PrEP, despite community estimates that more than 8000 gay men were likely to be using online PrEP by the end of 2017.

Instead the report defers to the ongoing IMPACT study (being coordinated by PHE) as the future indicator for judging PrEP efficacy. The report doesn’t acknowledge that many IMPACT study participants are likely to have been previously buying PrEP online. This change in access to PrEP rather than expansion to new PrEP users, by definition, will limit the ability of the IMPACT study to be a marker for the true impact of PrEP HIV incidence since 2017: many people who were already using PrEP are just continuing to use it in the study.

Finally, the report closes with an unhelpful sentence that ignores the scientific consensus that an undetectable viral load prevents HIV transmission. Instead, this PHE document ends with a reference to risk being “very unlikely”.

This language is both outdated and unhelpful, and it is out of place in a public report that should be rooted in both the latest evidence and PHE’s own otherwise excellent data. The evidence for U=U is now clear and accepted and like other national and international public health agencies, PHE should now clearly and consistently support this in its publications.

The reductions in HIV diagnoses are good news, but the UK still accounts for more than one-fifth of all new HIV diagnoses in EU/EEA countries. [3]

References

- PHE.Trends in new HIV diagnoses and people receiving HIV-related care in the United Kingdom: data to the end of December 2017. Health Protection ReportVolume 12 Number 32. PHE gateway number: 2018392. September 2018.

https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/hiv-annual-data-tables - PHE press release. New HIV diagnoses across the UK fell by 17% in 2017.(04 September 2018)

https://www.gov.uk/government/news/new-hiv-diagnoses-across-the-uk-fell-by-17-per-cent-in-2017 - European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. HIV and AIDS. In: ECDC. Annual epidemiological report for 2016. Stockholm: ECDC; 2018.

https://ecdc.europa.eu/en/publications-data/hiv-and-aids-annual-epidemiological-report-2016

https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/sites/portal/files/documents/AER_for_2016-HIV-AIDS.pdf (PDF)