8. 7 Randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trials

The most reliable evidence – often referred to as the ‘gold standard’ – comes from prospective randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled studies.

Randomisation

Randomising participants is the best proven way to allow for the fact that some things happen by chance – in studies just as in the rest of life.

Participants in a study are often randomised when two or more groups are are being compared.

This is used to balance factors in each group that could affect the study results. This includes known factors, such as sex, smoking status or social differences, and unknown factors such as genetic differences that we may not know anything about.

Randomising people, if done correctly, and especially with larger groups, should normally result in an approximate balance of all these factors.

This can sometimes be a difficult concept, but it is one of the most important things to understand.

Randomisation also stops bias when no-one in the study knows which participant goes to each group. This aspect of randomisation is called ‘blinding’.

- Single-blinding is when participants do not know which study arm they are in.

- Double-blinding is when neither the doctor nor the participant knows which arm they are in.

This prevents a doctor putting people who are most ill and in need of treatment into the group that receives an active drug rather than a placebo (dummy pill). If this happened, although this might sound more ‘fair’, the two groups would be different at the start, so you couldn’t compare the results accurately at the end.

By definition, clinical research involves different people getting different treatment. Often the people to get first access to a treatment in a trial, might not get the best results compared to people who use the drug after it is approved.

Joining a study is a balance of advantages and disadvantages.

Disadvantages for the first people using drugs may be that they do not use the best dose, or they risk resistance if other newer drugs aren’t allowed in the study.

The advantages may be that despite these problems, the drugs have still been life-saving, and the person is still alive to benefit from the next drugs in the pipeline.

Randomisation has to be done in a way that doesn’t select a certain group over another.

The most common example for randomising a participant to one of two groups is to toss a coin for each person – heads they join one group and tails they join the other.

This is because tossing a coin is random and can’t be predicted.

Over time, the more a coin is tossed, the more likely that approximately 50% will be heads and 50% will be tails.

An example of bad randomisation would be assigning participants who come to clinic on a Monday to one group and participants who come on a Tuesday to another.

In this example, people who come on Mondays may be different from people who come on a Tuesday, for social reasons. They may be more organised, or less likely to have a hangover from the weekend. These differences could unbalance the study results.

Study results should always report the most important characteristics of the people being studied. For example, this should include sex, gender, age, race, CD4 count and viral load, current health, education, etc.

Sometimes, even with randomisation, you may see that one group may have different characteristics.

When this happens the differences should be adjusted for in the final analysis. They need to be considered when interpreting the study results.

Blind and double-blind studies

Blinding (sometimes called ‘masking’) is the term to describe a doctor, patient or researcher not knowing which study group a patient has been assigned to.

A blinded study is where the participant doesn’t know which group they are in, or which treatment they are getting.

A double-blinded study is where neither the doctor nor the participant know which group the patient is in.

Blinding prevents different care or treatment being given based on the personal beliefs of either the doctor or patient.

An example of why blinding is important is that if someone know they are getting an active drug, both doctors and participants may be more likely to report side effects.

It could also affect how often a participant takes the treatment.

Placebo

A placebo is a dummy drug. It should look, smell and taste like the study drug, but not have any active ingredients.

Using a placebo helps find out whether the active drug is really active. It also helps interpret side effects.

If 10% of people in the active drug group report having a headache and 2% of people in the placebo group report a headache, then it is reasonable to think that the active drug can cause headaches.

If 10% of the placebo group also reported a headache, then it is reasonable to think that the active drug doesn’t cause a headache.

In a similar way, if viral load changes are the same in the active and placebo groups, this can prevent continuing to put participants at risk from using inactive drugs.

Control group

A control group refers to a group of participants in a study, that an intervention group is compared to.

This helps to show that the intervention actually caused what was seen and that it wouldn’t have happened anyway.

One common type of control group is to use a placebo.

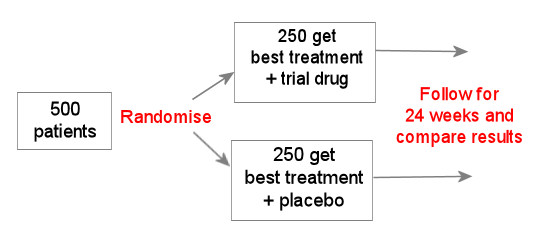

In the example above, all participants get the best treatment with or without the new drug.

If, for example, this is a new HIV drug and the best treatment already includes 3 active drugs, then it could be difficult to see any difference between the new drug and the placebo, because both groups will already do very well.

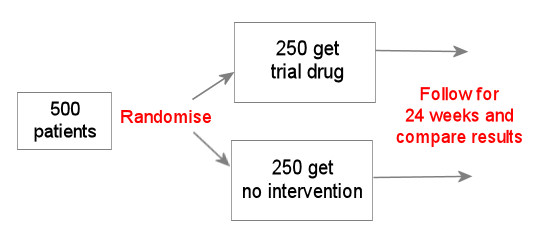

Another type of control group is a group where no intervention takes place.

This example might be used where there is something about the trial drug that makes using a placebo difficult – perhaps because it is given by injection.

The difficulty of not randomising the control group to having a placebo is that you can never be sure whether some of the things (both good and bad) that happened to participants in the active drug arm, are not due to chance.

More importantly, people in each arm may behave differently because they know they are getting the active drug rather than a placebo. This might make someone more likely to report more side effects.

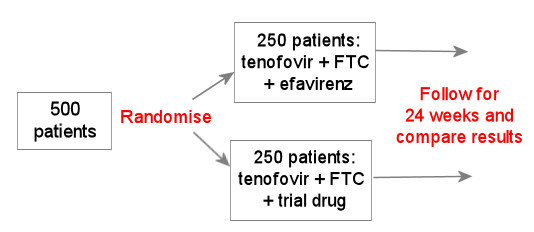

The example below uses a drug or combination that has already been studied as a control group.

This is still generally the type of study design used for studying a new HIV drug in people who have not yet used HIV treatment. This is generally okay, so long as the new drug turns out to be better than, or at least as good as, the current standard of care.

For this reason, early studies using this design should not enrol people who have advanced HIV (for example with CD4 counts less than 100 cells/mm3). These people will need to rely on a proven treatment.

Randomising participants should mean that important factors – both known and unknown – are likely to be distributed between each group. For example, having the similar numbers of women, Caucasians, smokers, CD4 counts etc in each group.

Last updated: 1 January 2023.