PrEP efficacy for transgender women: new analysis from iPrEX study

1 December 2015. Related: HIV prevention and transmission.

Simon Collins, HIV i-Base

Simon Collins, HIV i-Base

A new analysis from the large international iPrEX study that led to FDA approval of oral PrEP in the US provides additional results on efficacy in transgender participants. [1]

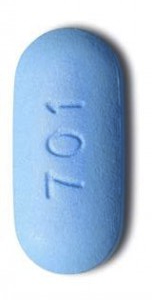

The results are important because even though HIV risk is often very high in transgender women due to a complex range of social factors, most PrEP studies only include a small number of transgender participants. In the paper described, published online in the Lancet on 5 November 2015, PrEP refers to oral tenofovir DF/FTC in a single pill.

Previous results from the iPrEX study [2, 3] and the follow-on open label extension (iPrEX-OLE) [4, 5] have been previously reported. The open label phase included additional dry blood spot pharmacokinetic (PK) monitoring for drug levels.

Background and demographics

The new analysis included 339 participants (14%) of the 2499 gay men and trans women enrolled in the randomised placebo-controlled iPrEX study. Of this group, 29 participants (1%) identified as women, 296 identified as trans (12%) and 14 (<1%) identified as men but also reported use of feminising hormones (oestrogen, progestogen or antiandrogen). The open label phase of iPrEX included 192 trans women, of whom 151 (74%) chose to take PrEP.

As background, the mechanism for PrEP efficacy was expected to be similar in transgender compared to cisgender men so long as PrEP is available and adherence is good. However, there is little data on whether hormone treatment changes biological risk or about interactions with drugs used for PrEP.

Transgender participants were from: Peru and Equador (n=247; 15% of participants in the region), Thailand (n=43; 38%), Brazil (38; 10%), US (n=6; 3%) and South Africa (n=5; 6%).

At baseline, there were significant social, demographic and HIV risk differences between trans and cisgender groups. Transgender participants had more sexual partners, less condom use for receptive anal sex, more reported sexually transmitted infections, greater use of cocaine or methamphetamines, lower formal education and were more likely to live alone and have a history of transactional sex compared to cis gay men (all p<0.0001).

Use of feminising hormones was reported by 67 (20%) of 339 trans women: 48 (16%) of 296 trans-identified participants, five (17%) of 29 women participants and 14 (0.6%) of 2160 participants who did not identify as either trans or women. Among 163 feminising regimens reported by 67 participants, 60 (37%) contained synthetic oestrogens, 58 (35%) contained natural oestrogens, 121 (74%) contained progestogens and 38 (23%) contained antiandrogens either alone or in combination with other hormones.

Results

In the main iPrEX study, in the transgender group there were 11 new HIV infections in active PrEP arm compared to 10 in the placebo arm (HR 1.1 [95% 0.5 to 2.7], p=0.77).

Although the ITT analysis showed no benefit of PrEP, when looking at infections in relation to PrEP use – defined by detection of drug levels – none of the people who seroconverted in the active PrEP arm had detectable drug levels at the time of infection (in either plasma or peripheral blood mononuclear cells). HIV incidence was zero (95%CI not calculable) if drug was detected and 4.9/100 patient years (95%CI 3.0 to 7.7) if not detected.

There were no infections when drug levels were equivalent to taking four or more doses per week. In the two women who became HIV positive during the open label phase, one had no detectable drug levels and one had levels associated with taking less than two doses per week.

The PK results matched drug levels in new infections to controls that remained negative and adjusted for HIV risk factors. During the open label phase, protective drug levels (>4 doses/week) were seen in a smaller percentage of the transgender group compared to gay men (18% vs 34%, p<0.003). This was irrespective of hormone use.

The efficacy results are important for two potential mechanisms where hormones might affect PrEP efficacy, although neither were reported as leading to lower efficacy in the results.

Firstly, although drug interactions with PrEP, might reduce PrEP exposure, the lower drug levels in transgender people compared to gay men in the study could not be separated from adherence.

Although the proportion of people with protective drug levels was lower in the trans vs cisgender groups, and also within the trans group by participants using hormones compared to those who were not, levels associated with 100% protection from taking four or more doses a week were still achieved by all subgroups.

It is important to note that these results provide no direct data on whether there is an interaction between hormones and PrEP because the study reports observed drug levels rather than drugs levels in relation to adherence.

Secondly, although hormones result in biological differences that affect HIV susceptibility in terms of anal and other tissue thickness, the use of these was suggested as a potential protective affect. In the discussion, the authors reported “whereas oestrogens preserve pelvic tissues including anal epithelium and reduce viral susceptibility in an animal model medroxyprogesterone acetate might decrease vaginal thickness and increase HIV susceptibility in non-transgender women its effect on anal epithelium is unknown. To the extent that feminising hormone regimens typically use oestrogens in place of or in addition to progestogens these hormonal effects might decrease HIV susceptibility overall.”

So while neither of this issues could be answered by this sub analysis from iPrEX, both issues should be assess in future prospective studies.

Comment

While there are many social and economic reasons why transgender people are at high risk of HIV, including reduced access to PrEP and other services as well as social factors that might have an impact on adherence, these results provide data that suggest that in the context of good adherence PrEP was effective in transgender people.

Even though this was an unplanned subgroup analysis that was not powered to be able to show efficacy difference between the transgender and cisgender groups, adherence with more than four doses was not associated with new HIV infections.

As with ART, HIV drugs used as PrEP are effective in both transgender and cisgender people. However, the paper rightly noted the high priority placed on hormone drugs for transgender people. [6]

It is now important to prioritise studies that provide data on the current knowledge gaps.

The research areas with data should not be used to limit access to PrEP for transgender people at risk of HIV infection.

References:

- Deutsch MB et al. HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis in transgender women: a subgroup analysis of the iPrEx trial. The Lancet HIV (2015). 2(12)e512–e519, December 2015(05 November 2015).

https://doi.org/10.1016/S2352-3018(15)00206-4 - Grant RM et al. Preexposure chemoprophylaxis for HIV prevention in men who have sex with men. NEJM. 23 November 2010

(10.1056/NEJMoa1011205). Free access:

http://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMoa1011205 - Collins S. Pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) with tenofovir/FTC reduces sexual transmission of HIV between men at high risk: results from the iPrEx study. HTB December 2010.

https://i-base.info/htb/14191 - Grant RM et al. Uptake of pre-exposure prophylaxis, sexual practices, and HIV incidence in men and transgender women who have sex with men: a cohort study. The Lancet Infectious Diseases. Early online publication, 22 July 2014. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(14)70847-3

http://www.thelancet.com/journals/laninf/article/PIIS1473-3099(14)70847-3/abstract - Collins S. Open label oral PrEP at four doses a week: why zero infections does not equal 100% efficacy. HTB August 2014.

https://i-base.info/htb/27161 - Radix A. HIV and vulnerable populations: transgender medicine. Invited lecture. 21st BHIVA Conference, 21-24 April 2015. Webscast:

http://www.bhiva.org/150424AsaRadix.aspx