Mpox: Q&A factsheet

1 November 2025. Related: News.

- In October 2025, the EU issued a caution about cases of mpox clade 1b in Europe. These cases were in gay and bisexual men who had no history of recent travel.

- Where available, including in the UK and the US, vaccination is still recommended.

- In 2023 and 2024 (up to 30 September 2024), there have been a total of 368 cases of mpox reported in the UK. [50]

- During 2022/23, almost 95,000 cases of mpox were reported globally in new countries. This included more than 4,700 in the UK, 7,500 in Spain, 11,000 in Brazil and 31,000 in the US (to October 2023).

This page is updated as new information becomes available. Last update 01 Nov 2025.

2024 – 2025: WHO emergency (clade 1b mpox)

On 14 August 2024, WHO declared mpox a health emergency of international concern (PHEIC). This was due to the rising cases of clade 1b reported in Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) and neighbouring countries. [48]

More details are included in this HTB report. [49]

The PHEIC was lifted in September 2025 although mpox is still a serious ongoing health issues in the contries most affected.

This news should not lead people in the UK to panic about a similar outbreak to 2022.

But it is good for people at risk of mpox to have a routine vaccine as part of good sexual health. People who only had one vaccine are still recommended to have a second shot. The time between shots is not important.

Information below is a refresher Q&A about mpox that was developed during the 2022 outbreak but is still just as relevant for clade 1b.

2024 update

Over the last year, there were only 102 cases of mpox reported in England and Wales. Mpox is still around though, just in very low numbers. [43, 44, 45]

This dramatic fall in cases is due to programmes to track, treat and vaccinate people at highest risk and because many people reduced their risk when cases were still very high.

Vaccines should still be available at sexual health clinics in England and Wales and hopefully other UK countries.

Protection against mpox on a population level comes from both individual immune responses in people who caught mpox and protection generated by vaccines. It is not yet known how long vaccine cover is likely to work and whether booster injections will be needed in the future.

Mpox is likely to still continue in some countries, especially in central Africa where there is still no access to treatment or vaccines. There is also the potential for local outbreaks to occur, perhaps linked to international travel.

Mpox is especially serious and sometimes fatal in people who have a low CD4 count linked to undiagnosed HIV. HIV testing is recommended before having the mpox vaccine, if you have not recently tested.

This page links to medical publications in 2024 about mpox. [47]

VACCINE ACCESS: Appointments for first mpox vaccines in England can be made online at two sites. Each vaccination site will have its own instructions on how to get an appointment.

- mpx.shl.uk (London clinics)

- nhs.uk/find-a-monkeypox-

vaccination (London and Manchester))

TECOVIRIMAT: the PLATINUM study of this promising treatment was stopped in November 2023 because there were too few cases for the study to enrol. See below:

In August 2024, a press release from the US NIH reported no benefit from tecovirimat in the PALM007 study running in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC). However, the manufacturer issued a press release saying that there might be benefits from early use in some people. [49]

Full data still need to be published.

Simon Collins, HIV i-Base and Alex Sparrowhawk, UK-CAB

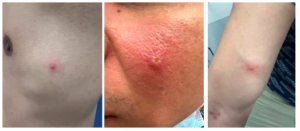

Mpox blister on a hand (US CDC)

This Q&A is about mpox (monkeypox).

Although monkeypox (mpox) is still rare in the general population, the risks are significantly higher among some gay and bisexual men.

The outbreak in 2022 was largely ended by the end of that year. However, awareness of mpox is still important.

The rapid spread of mpox globally in 2022 caused WHO to declare the pandemic a global health emergency, though this has since been rescinded. [30, 31, 32]

Since August 2022, case numbers in the UK began to steadily fall, largely because many people reduced their risk. By November 2022, only 5 to 10 cases a week were being reported in England and less than five cases were reported a week during 2023. This continued fall is also due to immune protection from exposure to mpox and from use of the vaccines.

The information below is organised into six sections.

- Mpox: first questions

- Prevention and transmission

- Testing, treatment and vaccination

- Mpox and HIV

- Other questions

- References and more information

1. Mpox: first questions

What is mpox?

Mpox is an infection caused by the monkeypox virus.

Although mpox is usually rare, since May 2022, more than 3700 cases of mpox were reported in the UK, mainly over the first four months. Nearly all cases were in gay and bisexual men.

Mpox has now been reported in more than 91,000 people globally, mainly in countries where mpox is not usually seen. International travel links cases to over 100 new countries. Highest numbers have been reported in the UK, Europe, the US and South America. Mpox has now reported in over 100 new countries.

The risk of mpox needs to be taken seriously. This is both for your individual health and so that it doesn’t become an established infection.

The original name monkeypox was not helpful. Monkeys are rarely affected and the name leads to additional stigma. In November 2022, WHO recommended using mpox. [42]

Is mpox easy to catch?

Depending on the circumstances, mpox is a highly infectious virus.

The current outbreak has mainly spread from direct skin contact. This can come from being in close contact with someone, whether or not you have sex.

See below for detailed information about risk and prevention.

Are there different strains of mpox?

Yes. Like most viruses there are different strains of the virus.

The two main strains are a mild form and a more aggressive form. The more aggressive form is now called Clade 1 and was linked to Central Africa. This milder form is now called Clade 2 and was linked to West Africa.

Luckily, the current global outbreak is with Clade 2b, the mild version. [41]

In November 2022, WHO renamed monkeypox as mpox. [42].

What are the main symptoms?

Many of the early general symptoms are similar to other infections like colds, flu and COVID.

These include fever, headache, muscle aches, backache, swollen lymph nodes, chills and feeling very tired.

Sometimes they are mild. And some people do not get symptoms at all.

Skin spots, ulcers or blisters develop at the same time or a few days after the symptoms above. This commonly starts as red skin bumps, often in the genitals or face. They can develop into blisters that can then break down into ulcers or sores. These develop a scab that eventually falls off.

The spots/ulcers can be in any part of the body. This can include in the mouth or in the genital area, including inside the anus.

Sores can be painful, aggressive and unpleasant. They can be itchy but it is important not to scratch. This could spread the virus to other parts of the body. If mpox infects the eyes this can be very serious.

What do spots/ulcers look like?

A few examples of ulcers are included below. Please click the picture to open larger view.

The examples below show different stages of the ulcers. They can vary in size from a few millimetres to a centimetre in diameter.

Other examples are included or linked below. Please click the picture to open larger view.

Other pictures can be found at this link to the US CDC.

https://www.cdc.gov/poxvirus/monkeypox/clinicians/clinical-recognition.html

Genital lesions are included in these two papers in the NEJM and the BMJ.

https://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMicm2206893 (NEJM)

https://www.bmj.com/content/bmj/378/bmj-2022-072410.full.pdf (BMJ)

Comprehensive photos for 20 cases at different timepoints are in the appendix of this NEJM paper. DOI: 10.1056/NEJMoa2207323. (21 July 2022).

https://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMoa2207323

How are the mpox ulcers different to other infections?

- Ulcers can be similar to several more common infections. These include chicken pox, syphilis, herpes, molluscum, cryptococcal infection, shingles (VZV) or even some heat rashes.

- Mpox ulcers are usually deeper and harder than seen with other infections

- Mpox ulcers can appear in crops every three to five days, and unlike chickenpox can take several days to evolve into blisters.

- Mpox ulcers often have a dip in the centre with a dot in the middle. This is called umbilicated.

How serious is mpox?

Most cases are mild or moderate, but this can still be difficult and painful. It also means self-isolating for at least three weeks.

With support, most people will be able to self-isolate at home. In the current outbreaks, 1 in 10 people (10%) need to be treated in hospital, usually to help manage pain.

Before the current outbreak, the number of spots was used to grade how serious an infection was.

- Mild infections can be uncomplicated with less than 25 spots or ulcers.

- Moderate infections involve 25 to 100 spots or ulcers.

- Severe infection is defined as having more than 100 ulcers, or more severe reactions.

- Roughly 1 in 100 cases can include serious complications.

However, the current outbreak has included very serious and painful complications needing hospitalisation with less than 25 spots or lesions. [35]

What complications can occur with mpox?

More severe infections are rare but can involve a wide range of symptoms and both internal and external areas of the body. [33, 34, 35]

- More than 100 spots or ulcers over several body sites.

- Inflammation of the lungs (pneumonitis), brain (encephalitis), eyes (keratitis) and bacterial infections.

- Severe and painful lesions in sensitive areas. This includes the mouth, throat, urethra, vagina, rectum and anus (proctitis), making daily functions difficult.

- Severe uclers that cause areas of skin to die (necrosis) sometimes needing surgery or amputation.

- Long-term complications related to damaged tissue. This can include scarring (including the face and genitals), narrowing the urethra (stricture) and a closed foreskin (phimosis).

- Sight-threatening infections in the eyes.

Some of these risks are linked to touching or scratching an ulcer and then touching or scratching another part of your body. Without careful treatment, sores that become infected with bacteria can cause septicaemia (blood poisoning).

Severe complications have been reported in people who are HIV negative and HIV positive. Risks are likely to be higher in people living with HIV who have a CD4 count less than 200 cells/mm3 or detectable viral load. This caution might apply to other people with reduced immune function, [35]

Serious infections need to be managed in hospital.

Is mpox an STI?

Currently, mpox is not defined as an STI. This is because even though the virus has been found in sexual fluids, infection is more likely to be through close physical contact, whether or not sex takes place.

Saliva is likely to be infectious. This means that kissing and oral sex could be the risk that explains transmission in sexual networks.

Any spots or ulcers will be very infectious.

Mpox can also be transmitted by contact with infected clothes, towels and bed linen.

Even if later research finds mpox is infectious in sexual fluids, the larger risk is likely to come from close contact.

Condoms, for example, will not generally protect against mpox. However, one exception might be if mpox remains in sexual fluids after the infection is otherwise cleared. This has been seen with other viruses, including Zika and Ebola.

Until there is more research, UK guidelines from 30 May 2022 recommend that people with confirmed mpox use condoms for eight weeks after the infection has cleared. This was extended to 12 weeks on 15 July, in line with WHO guidelines. [18]

People with mpox can also have their semen tested after 12 weeks, if this is something they want to check. [25]

Does mpox just affect gay men?

No, viruses do not care about sexuality.

Recent infections in gay men is because this is one of the networks of an early infection.

2. Transmission and prevention

What is the risk of catching mpox?

The overall risk of catching mpox was always generally low because mpox was always rare in the general population. It is also rare because case numbers are now very low.

However, during 2022 the risk was higher for gay and bisexual men who have multiple partners, or whose partners have a higher risk.

The most serious cases were people who were HIV positive but who had not yet been diagnosed or have a low CD4 count because they are not on ART. These cases can be fatal.

Knowing about the risk is now very important in settings where mpox risks are already high.

- Casual social contact is generally a low risk in all settings.

- Close contact can make the risk much higher. This includes with sexual partners and people you live with.

- The majority of cases in the current outbreak are linked to skin contact during sex. This is especially in settings where it is easy to have multiple new partners anonymously.

For these reasons, people diagnosed with mpox needed to self-isolate for 21 days, or until the infection cleared.

How is mpox transmitted?

Mpox can be spread in three main ways.

By close contact with someone who has symptoms.

The current outbreak is largely driven by skin-to-skin contact. This doesn’t need to be during sex, although this is also common. [40]

Mpox is especially infectious after symptoms have developed.

The spots/sores are highly infectious. The fluid in blisters and in the scabs contain very high amounts of mpox.

Skin contact with ulcers is likely the highest risk of catching mpox. However, some studies report that people can be infectious before symptoms and without symptoms.

By sharing sheets and towels.

Sharing sheets and towels with someone with mpox can also be a route of transmission.

Washing sheets and towels can also be a risk. This is in case infectious material is shaken into the air. A machine wash at a 60 degree cycle will be enough to sterilise sheets, clothes and towels.

Simple cleaning with regular cleaning products will be enough to sterilise surfaces, toilets and bathrooms. Diluted household bleach can be used but is not necessary.

However, mpox can remain infectious for more than 15 days on hard surfaces. This might be longer in soft material such as bedding and clothing. This US CDC leaflet has more information, including on cleaning. See references 12, 18 and 19.

The UKHSA has also produced guidelines for cleaning venues like saunas and venues where sex is allowed. [26]

In October 2022, US guidelines reported the mpox only remained infectious on hard surfaces that were frequently used. Examples from a hospital room included the handle of a soap dispenser and a towel. [39]

Through droplets in the air.

This usually involves spending extended time with someone in a room with poor ventilation. For example, spending more than 3 to 6 hours, where you are within two metres. Transmission by air is a much lower risk than for COVID-19 (or smallpox). [51]

So casual contact in the same room is a very low risk, unless someone was to directly sneeze in your face.

But transmission by air is a higher risk for people in the same household. This should involve taking special precautions to limit contact with people you live with.

How long after an exposure risk does mpox take to develop?

Based on the limited data, it can take from 1 to 3 weeks until mpox produces symptoms.

For most people this is 10 to 12 days after contact.

When is someone infectious?

The risk of onward transmission starts as soon as there are symptoms.

This is why it is important to call a doctor or clinic for advice. Please do not visit a doctor or clinic without calling first so this can be arranged properly. Otherwise health workers might also need to isolate.

The risk of transmission usually ends after the skin blisters and scabs have gone. However, even after mpox tests negative on swabs, blood and genital fluid can still test positive.

This is why the UK recommends using condoms for 12 weeks after the skin ulcers have been completely cured. [18]

What if I have been exposed to mpox?

Recommendations on recent risk depend on whether the risk is high, medium or low risk.

High risk is defined as close contacts of people who develop mpox. This includes being within six feet for more than three hours, sexual contact or direct contact with body fluids. It can also include contact with shared sheets and towels.

Please self-monitor for symptoms for the next three weeks. This can include taking your temperature twice a day which should stay below 38°C (100.4° F)

Seek medical advice if you develop any of the symptoms above, especially fever, rash, skin bumps, chills or swollen lymph nodes. In the UK this should be by calling a sexual health clinic or by calling 111.

People at higher risk might be offered PEP with vaccination. This will usually be from spending prolonged time with someone with diagnosed mpox or direct contact to ulcers or body fluids.This is only offered to people at high risk.

On 21 June 2022, the UKHSA announced that gay and bisexual men at risk of mpox would also be able to access the vaccine. Some sexual health clinics are now providing vaccines.

It is important to self-isolate if you develop symptoms and follow health care advice.

What does self-isolation involve?

More detailed information about mpox for people who are self isolating at home was published online in June 2022. It has been updated several times. [18]

Self isolation involves staying home and reducing contact with other people as much as possible. It involves avoiding public places and not seeing friends and family. Anyone you live with can be at risk. Sleep and eat in separate rooms and avoid close contact. The guidelines include detailed information about how to clean shared areas, towels and bedding.

You also need to isolate from pets. Someone from the Animal and Plant Health Agency (AHPA) will contact you about this.

If you need to leave your home for an emergency, any spots or ulcers need to be completely covered.

The guidance includes more details about when you can stop isolating. Also, additional safety measures like using condoms for the next 12 weeks. [18]

Please see this link for full details:

https://www.gov.uk/guidance/guidance-for-people-with-monkeypox-infection-who-are-isolating-at-home

This link it to an easy to read booklet about self-isolating at home.

https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/1100718/20220826-Monkeypox_people_who_are_isolating_at_home-Easy_read.pdf

Can I end self-isolation earlier

Yes, some people do not need to isolate for the full 21 days. If there are only a few lesions and they are completely covered, the need to self-isolate can be reduced. [18]

Many people might not be able to spend three weeks at home, for example if they are working and do not get sick pay. Or if they are not able to tell their employer about mpox, because of fear about stigma and discrimination.

Financial help to self-isolate is sometimes available from your local social services. It is easier to get in some places than in others. [18]

UK government advice says you can end self-isolation earlier in the following circumstances:

- You have not had a high temperature for at least 72 hours.

- You have had no new lesions in the previous 48 hours.

- All your lesions have scabbed over.

- You have no lesions in your mouth.

- Any lesions on your face, arms and hands have scabbed over, all the scabs have fallen off and a fresh layer of skin has formed underneath.

If you meet all of the points above, you may be able to stop self-isolating. Please contact your medical team for further advice.

You should continue to avoid close contact with young children, pregnant women and immunocompromised people until the scabs on all your lesions have fallen off and a fresh layer of skin has formed underneath. This is because you may still be infectious until the scabs have fallen off.

After your self-isolation has ended you should cover any remaining lesions when leaving the house or having close contact with people in your household. Do this until all the scabs have fallen off and a fresh layer of skin has formed underneath.

How can I reduce my risk and stay safe?

The current advice for how to reduce your risks is likely to change every week.

This will depend on how successfully mpox is contained or on whether cases continue to rise. This might mean this advice changes, depending on where you live and in different social situations.

This also involves a personal approach to healthcare both for yourself and for the community. For example, to get medical advice if you feel unwell or develop unexpected skin bumps or ulcers. This will also help you access the best care to recover quickly.

One of the higher risks comes from contact with sexual partners, So reducing the numbers of partners, especially in a group setting will help. This is especially important at gay and bisexual venues in London. For example higher risk situations include:

- Private sex parties.

- Saunas, backrooms and sex-on-premises venues.

- Outdoor cruising areas at night.

- Any situation where is is easy to have close contact with multiple sex partners.

Social events that involve being with many people for hours in a poorly ventilated space will be a higher risk than outdoor events with fewer people. This is whether or not anyone is having sex.

This will hopefully only for a short time, perhaps only for the next few weeks.

Will having mpox once protect me against catching it again?

There is currently not enough information to answer this question.

Even if it is possible, this would not be something to rely on before we have data.

Also, cases have been reported when mpox returned after the infection was thought to be cured. When this happens, special tests are needed to know whether this is a new or relapse infection.

3. Testing, treatment and vaccination

What if I have symptoms?

If you are worried about symptoms, please telephone a sexual health clinic (or 111 in the UK).

Contact by phone is important. The clinic will ask you about symptoms, including to describe any spots or skin blisters.

Please do NOT visit the clinic using a drop-in service. This could cause health workers to need to isolate and staffing is already under pressure.

Anyone in the UK can access free testing and treatment at a sexual health clinic.

How is mpox diagnosed?

If distinctive spots/blisters appear a few days after other general symptoms, mpox is very likely, even before it is confirmed by a test.

This will involve a doctor checking that the skin bumps and blisters are not another infection.

However, testing is still important to rule out other pox viruses.

PCR testing is used to confirm mpox. This involves sending samples to a UK-HSA laboratory. The doctor will need to have your contact details so they can let you know the test result. The UK-HSA is responsible for all mpox cases.

If the sample tests positive, you will be asked about close contacts over the previous three weeks. This includes people you live with and any sexual partners. Sexual partners will not be told about you.

All information is handled privately but please talk to your doctor if you have questions about this.

How important is contact tracing?

Anyone diagnosed with mpox will be asked for details about people they have been in close contact with.

This helps to contact people who might be at risk who may benefit from PEP. Effective contact tracing could limit how many other people contract mpox. This is a specialist part of sexual health care.

People at high risk can then self-monitor for symptoms over the next three weeks. They will be monitored with a daily phone call, and they may be offered the mpox vaccine.

Can mpox be treated?

Yes.

The main treatments are treatments to reduce pain and to reduce the risk of scaring. This involves expert advice from pain management and skin clinics.

An antiviral drug called tecovirimat is also being increasingly used in the UK, especially if symptoms are difficult.

Tecovirimat (brand name Tpoxx) is a pill that is taken twice daily for 2 weeks. The dose depends on your weight and tecovirimat needs to be taken with a high fat meal. It is approved in the US to treat smallpox, but based on very limited data. [29]

In August 2024, early data from the PALM007 study in DRC suggested limited if any impoact of tecovirimat. [49]

Studies using tecovirimat are already running in the UK (PLATINUM study) and US (STORM study). These studies randomise people with mild mpox to either tecovirimat or placebo (dummy pill). People with severe mpox should be able to get tecovirimat outside these studies. [35]

The PLATINUM study doe not need any clinic visits. Your doctor only needs to email the study team. (www.platinumtrial.ox.ac.uk/healthcare-workers2).

Two other meds – brincidofovir and cidofovir – are no longer being used in the UK. This is because they are not effective and have a high risk of side effects.

As most infections are mild, tecovirimat was originally only given to more severe cases, or to people at higher risk of severe infection.This can include people with reduced immunity, children younger than eight, pregnancy, and selected other infections.

Vaccines are also being used to manage and reduce the symptoms from infection.

How can I manage symptoms if I am isolating at home?

The following suggestions can help manage symptoms and reduce pain.

- Salt water bathing can help reduce the risk of infection and can help ulcers recover more quickly.

- Anaesthetic gels (lidocaine, including brand name Instillagel) can help reduce local pain.

- Over-the-counter pain killers like paracetamol and ibuprofen can reduce pain throughout the body.

- If paracetamol and ibuprofen are not working, try codeine. Stronger formulations can be prescribed by your doctor. This might also involve taking laxatives, if needed.

- Over the counter antihistamines and calamine lotion can both help to reduce itching, If calamine lotion is not available alternatives include crotamiton cream (brand name Eurax) and aloe vera gel. Apparently there is a national shortage of calamine lotion.

- Medicated waterproof spot plasters can be used to cover individual ulcers on your skin. This can protect you from scratching or knocking them. It can also limit risk of transmission (to yourself or others).

Please talk to your GP and/or the sexual health clinic to make sure any pain is managed properly. Severe pain can sometimes be managed better in hospital.

Are there any long-term effects from mpox?

Most people return to daily life after the lesions have fully healed, especially after mild cases.

Even though long-term information is limited, scars or skin colour changes have been reported after severe lesions have healed. A skin doctor can prescribe creams that might help.

Some people report being psychologically affected by the experience of mpox. This includes needing time to regain confidence with sexual partners. [37]

Severe symptoms from mpox might be more complicated, for example if there were neurological problems.

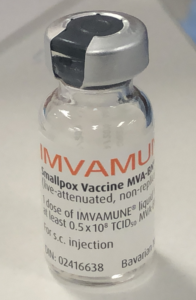

Which vaccine is being used against mpox?

The mpox vaccine is called Imvanex (also called Imvamune, Jynneos and MVA).

The mpox vaccine is called Imvanex (also called Imvamune, Jynneos and MVA).

It is a live but non-replicating vaccine that was approved in 2013 in Europe and in 2019 in the US. This vaccine is safe to use by people living with HIV. It is given in two doses, 28 days apart.

Although the vaccine is safe, anyone with a CD4 count below 100 might be unlikely to generate an effective response.

Information on the Imvanex vaccine from the UKHSA. and the EMA. [27, 28]

An earlier vaccine called ACAM2000 was approved in 2007 but is a live replication-competent vaccine. Although it is given as a single dose it is not recommended in people living with HIV. It is also no longer available in the UK.

Is the mpox vaccine effective?

Yes, the Imvanex vaccine is likely to help even if given after you have been in contact with mpox. It should limit the risk of infection or limit the severity of illness if the infection develops.

The vaccine might be up to 95%. This is based on receiving two shots, 28 days apart. It also involves waiting another two weeks for the vaccine to work (ie six weeks after the first shot.

Protection after each shot might take up to four weeks to develop. It will be lower after only a single shot.

It might also take longer to develop and be lower in people living with HIV.

The limited vaccine supply means that most people will just start with a single shot.

For more information about vaccine efficacy, please see: How good is the monkeypox vaccine?

https://i-base.info/qa/20255

Vaccination for close contacts is most effective when given within four days of contact. However, it might still be effective for up to 14 days after.

Will smallpox vaccinations from childhood still be active?

Many adults older than 50 will have had the smallpox vaccine as a child.

Childhood vaccination doesn’t prevent mpox infection now. We know this because many of the reported cases were in people who were vaccinated as a child. [36]

Smallpox vaccinations were stopped in the UK in 1971 and immune responses become lower after 10-20 years. As with COVID vaccines, cellular immune responses might last for much longer.

However, childhood vaccination might produce a stronger immune response from the mpox vaccine.

Are vaccines available as PrEP, including to gay and bisexual men?

From July 2022, the UK and some other countries are offering vaccines to protect people at high risk.

This can include close contacts of people diagnosed with mpox, including household contacts.

Key health workers are also be offered a vaccine. This is because they could be at higher risk of contact from people who have not yet been diagnosed with MPOX.

On 21 June, the UK announced that some gay and bisexual men would be offered the vaccine. However, there are limited vaccines supplies (currently only 20,000 doses). Some sexual health clinics now let people book vaccine appointments online. These places are still limited and go very quickly.

A single injection is about 45% effective. This increases to 85% after two injections, given 28 days apart.

4. HIV and mpox

How does HIV affect mpox?

The British HIV Association (BHIVA) published a recent statement on mpox, that has also been updated.

This says that HIV should not increase your risk of catching mpox. It also should not make mpox a more serious.

So far, HIV is not linked to any difference in symptoms and outcomes. This is based on you having an undetectable viral load and a CD4 count that is well above 200 cells/mm3. This is a cautious approach because there is too little direct evidence about this.

However, roughly half over the mpox cases have been in men who are living with HIV.

The BHIVA statement also references a Nigerian study with worse outcomes for people living with HIV. Most of these cases were not on effective ART though, some with very low CD4 counts and most with detectable viral load.

Please see this link to BHIVA and ECDC statements about mpox.

https://i-base.info/htb/42896

5. Other questions

What are the differences between mpox and COVID?

Although everyone will worry about the similarities to COVID-19.

There are important differences that will stop mpox from becoming a pandemic.

- mpox only becomes infectious after there are symptoms. COVID was devastating because it was infectious several days before anyone had symptoms.

- mpox is heavier than the COVID virus. This makes it more likely to fall to the ground rather than stay in the air where it can be breathed in.

- COVID infection was through the nose, throat and lungs. Although MPOX can be caught from droplets in air in a confined space, but is more commonly caught by skin to skin contact.

- mpox is much less likely to mutate into different strains than COVID.

- COVID was a more severe infection for more people. Many people needed time in intensive care and people of all ages died. Although MPOX can be very serious, less than 20 people have died.

What about transmission to animals?

This is an important concern with mpox.

Despite the name, mpox is more linked to infections in other animals. This includes in mice, rats and squirrels.

An outbreak in the US in 2003 was linked to prairie-dogs (which are not dogs).

The concern about other animals being carriers for mpox is that this might make it difficult to control the virus in the long-term.

It is also important for people who self-isolate at home to know whether this also needs to be from their pets. Advice was not initially given on this question. However, on 27 May the UK included the need for people diagnosed with MPOX to also isolate from their pets. Similar guidance is made by the ECDC.

This is to reduce the risk that animals could become a long-term reservoir for mpox.

Gerbils, hamsters and other rodents have a very high risk of catching MPOX. Other pets including cats and dogs should be kept isolated at home. However, it is difficult to set how “regular vet checks to ensure no clinical signs are observed” is expected to work.

People with pets will be contacted by the Animal and Plant Health Agency (APHA) with with more information.

https://www.gov.uk/guidance/guidance-for-people-with-monkeypox-infection-who-are-isolating-at-home

How worried should we be about mpox?

WHO responded quickly to the recent news about mpox with two early reports on 21 and 30 May 2022. These recognised the next few weeks would be very important. On 23 July 2022 WHO classified mpox as a global health crisis.

With more that 82,500 cases now reported in more than 100 non-endemic countries, mpox is now a global crisis. The rapid increases in cases in the UK, Spain, Germany, France and the US is likely to be repeated in other high income countries with similar social structures for gay and bisexual men.

Many are unlikely to have the same resources and access to vaccines that are now being used for prevention. This makes it likely that international travel will continue to spread mpox.

Although mpox can generally be managed at home, it can be a very nasty and painful infection. About 1 in 10 cases are more severe and are managed in hospital, especially for pain.

Since late August, numbers have started to fall in the UK and some other countries. It is not yet clear whether this is mainly due to people reducing their risk or because of the vaccines.

Even with fewer cases, vaccine programmes will continue. It is still important to be aware of mpox risks. Mpox is also likely to continue to affect high risk situations from international travel.

Unfortunately, more than 160 people have died from severe complications of mpox in the current outbreak. These mostly occurred in the US (55), Mexico (32), Peru (20), and Brazil (16). Deaths are also reported in some African countries including Nigeria (9), Ghana (4), Cameroon (3), and DRC (2).

6. References and further information

The following sources were used for the information on this page and/or are useful links for further information.

References are not in chronological order as updates to this page have added new references at the end.

- NHS. Monkeypox.

https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/monkeypox

Non-technical information about MPX in the UK. This includes who to contact if you are worried about symptoms. - UK Health Security Agency (UK-HSA). Monkeypox virus. (9 August 2022).

https://www.gov.uk/guidance/monkeypox

More detailed information from the UK government about all aspects of MPX including update on the current outbreak. - BHIVA rapid statement on monkeypox virus. (17 May 2022, updated 31 May 2022).

https://www.bhiva.org/BHIVA-rapid-statement-on-monkeypox-virus - European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC). Monkeypox multi-country outbreak: rapid assessment report. (23 May 2022).

https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/publications-data/risk-assessment-monkeypox-multi-country-outbreak (download page)

https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/sites/default/files/documents/Monkeypox-multi-country-outbreak.pdf (PDF)

See also this slide set from an informal webinar given on 24 May 2022.

Monkeypox ECDC webinar (PDF) - Adler H et al. Clinical features and management of human monkeypox: a retrospective observational study in the UK. The Lancet, DOI: 10.1016/S1473-3099(22)00228-6. (May 24 2022).

https://www.thelancet.com/journals/laninf/article/PIIS1473-3099(22)00228-6/fulltext

Details of seven MPX cases reported in the UK between 2028 and 2021. - US CDC. What clinicians need to know about monkeypox in the United States and other countries.

https://emergency.cdc.gov/coca/calls/2022/callinfo_052422.asp

This US talk on clinical management includes pictures of MPX compared to other common skin reactions. - US CDC. Monitoring people who have been exposed.

https://www.cdc.gov/poxvirus/monkeypox/clinicians/monitoring.html - US CDC. Home page for information for doctors about MPX.

https://www.cdc.gov/poxvirus/monkeypox/clinicians/index.html - International Monkeypox case tracker. [Kraemer MUG et al. Lancet Inf Dis, DOI: 10.1016/S1473-3099(22)00359-0]

https://monkeypox.healthmap.org - Human Animal Infections and Risk Surveillance group (HAIRS). Qualitative assessment of the risk to the UK human population of monkeypox infection in a canine, feline, mustelid, lagomorph or rodent UK pet. (27 May 2022).

https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/hairs-risk-assessment-monkeypox/qualitative-assessment-of-the-risk-to-the-uk-human-population-of-monkeypox-infection-in-a-canine-feline-mustelid-lagomorph-or-rodent-uk-pet - Prepster and the UK Health Security Agency (HSA). Two UK Community webinars available online.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9_xz-KTMpHk (26 May 2022).

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=I0o8FG5MYLw (6 June 2022).

Two excellent early community discussions. - UK Health Security Agency (UK-HSA). Principles for monkeypox control in the UK: 4 nations consensus statement. (30 May 2022).

https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/principles-for-monkeypox-control-in-the-uk-4-nations-consensus-statement/principles-for-monkeypox-control-in-the-uk-4-nations-consensus-statement

Includes updated guidelines for continued prevention in the UK. - WHO. Multi-country monkeypox outbreak in non-endemic countries: Update. (29 May 2022).

https://www.who.int/emergencies/disease-outbreak-news/item/2022-DON388

Detailed review of international cases and guidelines for appropriate monitoring and prevention. - EACS/ECDC. Informal webinar given on 24 May 2022.

Monkeypox EACS/ECDC webinar 1 (PDF) - EASC/ECDC. Informal webinar given on 31 May 2022.

Monkeypox_EACS/ECDC_webinar 2 (PDF) - Andrea A et al for the INMI Monkeypox Group. Epidemiological, clinical and virological characteristics of four cases of monkeypox support transmission through sexual contact, Italy, May 2022. Euro Surveill. 2022;27(22):pii=2200421. (2 Jun 2022).

https://doi.org/10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2022.27.22.2200421. - Monkeypox Outbreak — Nine States, May 2022. Minhaj FS et al. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2022;71:764–769. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm7123e1.

- UK Health Security Agency (UK-HSA). Monkeypox: infected people who are isolating at home: Information for people who have been diagnosed with a monkeypox infection and who have been advised to self-isolate at home. (9 June 2022).

https://www.gov.uk/guidance/guidance-for-people-with-monkeypox-infection-who-are-isolating-at-home - US CDC. Disinfection of the home and non-healthcare settings. (6 June 2022).

https://www.cdc.gov/poxvirus/monkeypox/pdf/Monkeypox-Interim-Guidance-for-Household-Disinfection-508.pdf (PDF) - Patrocinio-Jesus R et al. Monkeypox Genital Lesions. NEJM. DOI: 10.1056/NEJMicm2206893. (15 June 2022).

https://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMicm2206893 - UK plans to offer vaccine to gay and bisexual men at risk of monkeypox. HTB (21 June 2022).

https://i-base.info/htb/43164 - UKHSA press release. Monkeypox vaccine to be offered more widely to help control outbreak. (21 June 2022).

https://www.gov.uk/government/news/monkeypox-vaccine-to-be-offered-more-widely-to-help-control-outbreak - Grosenbach DW et al. Oral tecovirimat for the treatment of smallpox. N Engl J Med 2018; 379:44-53. DOI: 10.1056/NEJMoa1705688. (5 July 2018).

https://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/nejmoa1705688 - JAMA. Global monkeypox outbreaks spur drug research for the neglected disease. JAMA review. doi:10.1001/jama.2022.11224. (29 June 2022).

https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jama/fullarticle/2793925 - Monkeypox: semen testing for viral DNA (15 July 2022).

https://www.gov.uk/guidance/monkeypox-semen-testing-for-viral-dna - UKHSA. Monkeypox: cleaning sex-on-premises venues. (8 June 2022).

https://www.gov.uk/guidance/monkeypox-cleaning-sex-on-premises-venues - UKHSA. Protecting you from monkeypox – information on the smallpox vaccination. (8 July 2022).

https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/monkeypox-vaccination-resources/protecting-you-from-monkeypox-information-on-the-smallpox-vaccination - EMA. Patient information on imvanex vaccine.

https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/medicines/human/EPAR/imvanex - Merchlinsky M et al. The development and approval of tecoviromat (TPOXX), the first antiviral against smallpox. Antiviral Res. 2019 Aug;168:168-174. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2019.06.005. Epub 2019 Jun 7.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6663070/ - WHO. Second meeting of the International Health Regulations (2005) (IHR) Emergency Committee regarding the multi-country outbreak of monkeypox. (23 Juy 2022).

https://www.who.int/news/item/23-07-2022-second-meeting-of-the-international-health-regulations-(2005)-(ihr)-emergency-committee-regarding-the-multi-country-outbreak-of-monkeypox - BBC news. Monkeypox: WHO declares highest alert over outbreak. (22 July 2022).

https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/health-62279436 -

CNBC news. WHO declares rapidly spreading monkeypox outbreak a global health emergency. (22 July 2022).

- Lucer J et al. Monkeypox virus–associated severe proctitis treated with oral tecovirimat: a report of two cases. Letter. Annals Internal Medicine. doi.org/10.7326/L22-0300. (18 August 2022).

www.acpjournals.org/doi/10.7326/L22-0300 - Patel A et al. Clinical features and novel presentations of human monkeypox in a central London centre during the 2022 outbreak: descriptive case series BMJ 2022; 378 doi: 10.1136/bmj-2022-072410. (28 July 2022).

https://www.bmj.com/content/378/bmj-2022-072410 - Tecovirimat for treating mild monkeypox: new studies open in the UK and US. HTB (1 September 2022).

https://i-base.info/htb/43758 - International study of 528 monkeypox (MPX) cases: results from the 2022 outbreak need to inform new management guidelines. HTB (3 August 2022).

https://i-base.info/htb/43458 - NBC News. Life after monkeypox: Men describe an uncertain road to recovery. (26 September 2022).

https://apple.news/AF1JJfgO2RamrojiAUZr_KQ - US CDC. Severe manifestations of monkeypox among people who are immunocompromised due to HIV or other conditions. (29 September 2022).

emergency.cdc.gov/han/2022/han00475.asp - US CDC. Science Brief: Detection and Transmission of Monkeypox Virus. (18 October 2022).

https://www.cdc.gov/poxvirus/monkeypox/about/science-behind-transmission.html - Levels of monkeypox viral load in different body sites supports highest risk from body contact. HTB (3 October 2022).

https://i-base.info/htb/44154 - Mitjà O et al. Monkeypox. Review, The Lancet. (17 November 2022).

https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(22)02075-X - WHO. WHO recommends new name for monkeypox disease. (28 November 2022).

https://www.who.int/news/item/28-11-2022-who-recommends-new-name-for-monkeypox-disease - UKSHA. Monkeypox outbreak: epidemiological overview. (22 December 2022).

https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/monkeypox-outbreak-epidemiological-overview - UKSHA. Notifications of infectious diseases (NOIDs) causative agents weekly report. (3 January 2023)

https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/notifiable-diseases-causative-agents-reports-for-2022 - UKSHA. Notifiable diseases: last 52 weeks,

https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/notifiable-diseases-last-52-weeks - UKHSA press release. People still eligible for mpox vaccine urged to come forward. (22 March 2023).

https://www.gov.uk/government/news/people-still-eligible-for-mpox-vaccine-urged-to-come-forward - HTB, Mpox updates: recent publications (2024)

https://i-base.info/htb/47082 - WHO. WHO Director-General declares mpox outbreak a public health emergency of international concern. (14 August 2024)

https://www.who.int/news/item/14-08-2024-who-director-general-declares-mpox-outbreak-a-public-health-emergency-of-international-concern - HTB, WHO declare new mpox emergency (clade 1b). (16 August 2024).

https://i-base.info/htb/48410. - UKHSA. Mpox (monkeypox) outbreak: epidemiological overview, 8 August 2024.

https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/monkeypox-outbreak-epidemiological-overview - Leong FY et al. Aerosol transmission risk of mpox relative to COVID-19 and smallpox. Lancet Microbe. 2025 Feb 6:101082. doi: 10.1016/j.lanmic.2025.101082.

https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lanmic/article/PIIS2666-5247(25)00010-2/fulltext

This information was posted on 26 May 2022 and is updated as new information becomes available. Last update 29 August 2024.